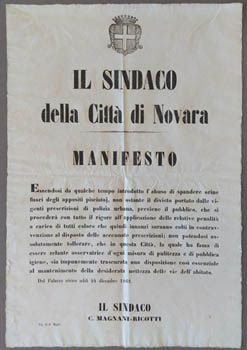

Urine. Carlo Magnani-Riccoti. Il Sindaco della Citta di Novara - Manifesto. Novara, Miglio 1862. Broadside 56x39cm tipped on card. Old folds, a nice copy. Au$200

Magnani-Roccoti, first mayor of modern Novara, warns the citizens of Novara that the piss sodden streets of the city will be tolerated no more and that police will prosecute with utmost rigour anyone sploshing urine around the place. I wonder whether the urine issue was related to the recent invention of a beverage by Signor Campari of Novara. And I wonder why the existence of a manifesto against piss strikes me as irresistible.

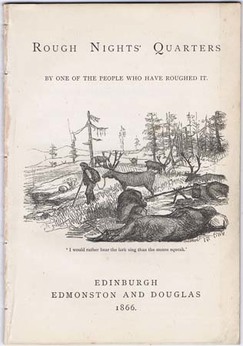

Rough Nights' Quarters. By one of the people who have roughed it. Edinburgh, Edmonston and Douglas 1866. Octavo disbound; 32pp, title vignette. A mild darker stripe along the front edge where it must have been bound with something smaller. Au$100

This is a spluttering response to an expose in the Pall Mall Gazette for which an undercover reporter spent 'A Night in a Workhouse'. There is more to it but I finished this pamphlet with the notion that the upright British homeless are a tougher breed than the milksop reporter and any that weren't just needed a decent public school education followed by a hunting expedition to toughen them up.

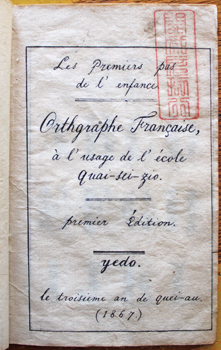

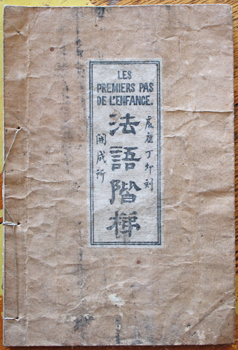

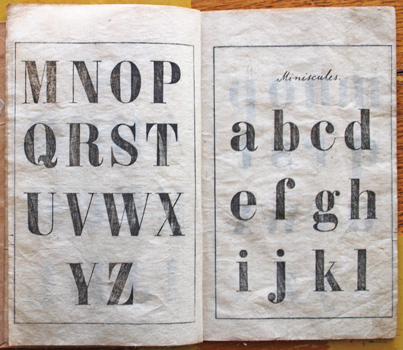

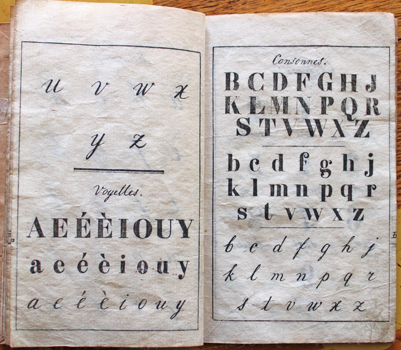

Les premiers pas de l'enfance. Orthgraphe Francaise, a l'usage de l'ecole quai-sei-zio. Premier edition. Yedo ... (1867). [sic]. Yedo (Tokyo), 1867 (Keio 3). 18x13cm publisher's wrappers with printed label (marked, stitching broken); 32pp including 10 pages of alphabets. Pretty good. The red stamp on the title is the school's. Au$300

The Kaiseijo (quai-sei-zio or Kaisezio or Kaiseizyo or Kaiseidzio or Kaiceizio depending on who wrote it) was the Bakumatsu school for barbarian studies, founded in 1857 and re-named in 1863. In 1865 the military joined in with this maybe unwelcome but necessary education and, I've read, quadrupled the number of students with 300 learning English and 100 learning French. It seems they began printing their own texts in 1866. Come Meiji it became the Kaisei gakko and eventually part of the conglomerate that became Tokyo University.

It's easy for blinkered anglophones like me to forget that the Japanese were busily digesting the whole planet, not just learning fractured English from absurd phrase books. They learnt many fractured languages from absurd texts and still somehow leapt into the modern world.

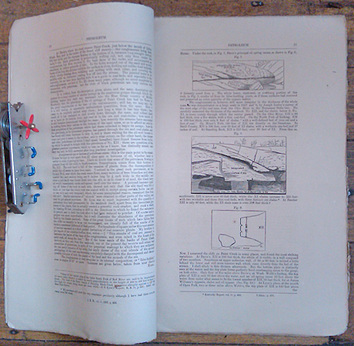

Oil. Petroleum. (Correspondence, &c., Respecting Existence of, in New South Wales.) Sydney, Govt Printer 1867. Foolscap folio sewn as issued (a bit used); 22pp, litho map & 2 plates, illustrations through the text. Au$750

The first publication of any note on petroleum in Australia, or at least the possibility of it, and necessary investigations, results of examinations, and so on. The search seems to have been kicked off in 1866 by William Fane de Salis sending out a copy of Lesley's 1865 paper on the Kentucky petroleum basin, "the only paper as yet published giving any reliable scientific account of the strata," in the hopes that comparative work could be done. That paper is reprinted here, from the copy kindly given by Murchison.

What is not in this paper but is in the columns of The Empire is that the Minister for Lands ignored the offer of de Salis and that a Lands Department clerk responded, "the Minister for Lands does not consider it advisable to republish Mr Lesley's pamphlet as proposed by you". Neither would the Lands Department, 'this incubus,' release Lesley's paper for The Empire to print, prompting the outraged columnist of The Empire to mutter darkly about the ''little games played some time ago in the matter of certain mineral lands at Illawarra.'' ''Is there a disinterested and intelligent man in the colony who does not believe in his heart that the blowing of the Lands Office into perdition, with all its accumulated stores of red tape, useless maps, and sickening arrears of correspondence, would be one of the best things that could happen for the welfare of the community?"

All this is not quite true, the correspondence in this paper tells a slightly different story but still, in all this is an education in the power of print, most obvious in the ability of the press to push along a recalcitrant bureaucracy. But more interesting is the potency held by what was considered the sole copy of an otherwise unobtainable pamphlet. Lesley's paper itself is rare, certainly it was missed by Swanson's bibliography of oil and gas. It's almost unnecessary to add that this Australian paper also doesn't appear.

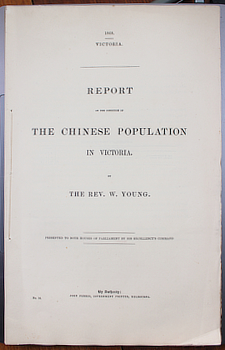

YOUNG, Rev. W. Report on the Condition of the Chinese Population in Victoria. Melbourne, Govt Printer 1868. Foolscap folio, stitched as issued; 30pp. Au$850

By 1868 the Chinese population of Victoria was on the wane - estimated at less than half of its peak at the height of the goldrush - but "vicious practices"were seemingly on the rise. Chief among these were, of course, gambling and opium but their by-products, larceny and robberies, were a growing threat. Young suggested that the decline or disbandment of Chinese Associations had a directly negative effect on crime and has provided a translation of the rules of an association to illustrate to the government the benefit of these associations to the community.

The first part of his report is both valuable and touching in that Chinese translators have provided statistics for each of the areas with Chinese communities; these statistics then are personal and idiosyncratic in their focus, providing the closest thing we have to a Chinese view of themselves at the time. Young includes a report by Dr Clendenning on the condition of Chinese lepers at Ballarat, and then finishes with his own report and suggestions for improvements, including the restitution of 'Headmen', the improvement of interpreters, education in English, Chinese police officers and so on. However, given the "abnormal condition of the great mass" (ie no women), in present circumstances it was best to encourage them to all go home.

Young was an LMS missionary to the Chinese, apparently of Scottish-Malay descent, who had served in Amoy before coming to Victoria in the mid fifties. The impression given by this report and other documents of the period is that he was one of very few non-Chinese in the colony that had any grasp of any Chinese language.

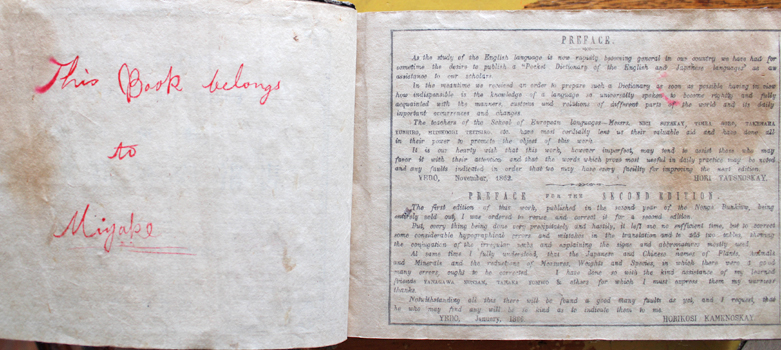

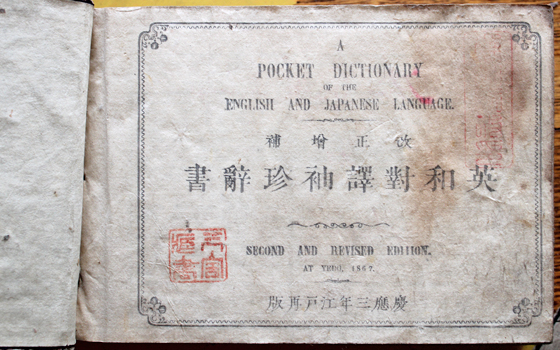

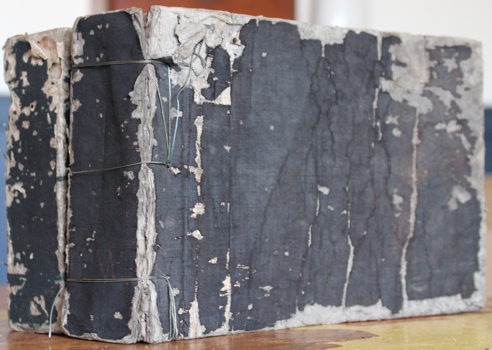

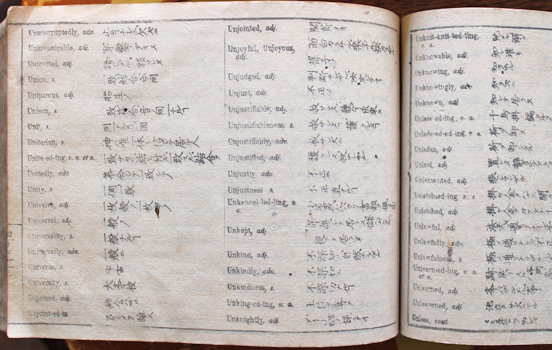

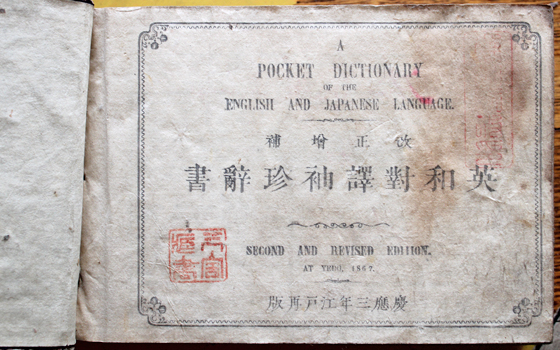

Tatsunosuke Hori et al. A Pocket Dictionary of the English and Japanese Language. Second and revised edition. At Yedo 1867. Tokyo, Kuradaya Seiemon 1869 (Meiji 2). Two volumes 15x22cm contemporary limp boards (battered, stitching broken but all solid enough). Stains, mostly at each end and some fairly mild worming at the very end. Sensibly divided into two volumes toward the end of N. Used but comparatively handsome copy of a book usually found as an incomplete wreck. Inscription in red on the back of the title: "This Book belongs to Miyake" and Miyake ownership seals and inscription at the end. Au$1100

Actually a new printing of the 1867 edition as, I suspect, are several of the copies catalogued by folk who haven't looked properly at the very end of the book. Tatsunoske's first edition appeared in 1862; apparently 200 copies were printed. A second revised edition arrived in 1866 and the 1867 printing has the English type newly made into wood blocks. Then comes our 1869 printing with the notice of approval (1869) on the last page and Kuradaya's name inside the back cover. And the Kaiseisho - the Bakumatsa school - seal on the tile and/or at the end has been changed for the Tokugawa seal. If you want to get fussy: this is type B of the colophon designated by Tomo Endo in his census of copies in Eigakushi Kenkyu (2006).

It seems accepted that this was the first English-Japanese dictionary. The Angeriagorian Taisei was compiled in 1814 but that has been dismissed as a word book - a mere 6000 words - and was only circulated in manuscript among the chosen few. A Japanese-English dictionary followed ours a few years later.

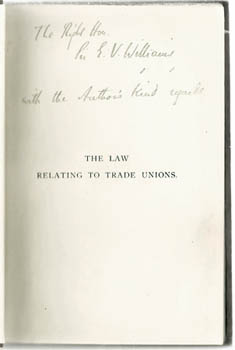

ERLE, Sir William. The Law Relating to Trade Unions. London, Macmillan 1869. Octavo publisher's cloth, ix,92pp. A presentation from Erle to fellow judge Sir Edward Vaughan Williams. Au$150

Begun as part of the Trade Union Commission to ascertain the state of existing laws, the work grew "beyond the immediate scope of our commission" and is here published separately. "Many of the principles were obtained by my own induction .. I intended .. to state the law as it is, and only rarely express an opinion as to what the law ought to be." This was really a primer for the other commissioners.

"A very lucid exposition," says the DNB but the reviewer for The Spectator differed vehemently. Erle received a thorough thrashing for his appalling style and grammar which, rather than hiding clear thought displayed too clearly the "looseness of his thought". A week later the same writer (J.M.L. - a champion of labour) returned to deliver another drubbing to Erle and this book, this time sounding an alarm about the wider dangers of Erle's specious claim to have published an opinion free book before the Commission's report was finished.

Erle is credited with being the formative influence of the 1871 Trade Unions Act which redressed the illegality of trade unions in law - credit that seems undeserved in many ways as the liberality of the act is the legacy of the minority report. And I bet J.M.L. would have something to say about that.

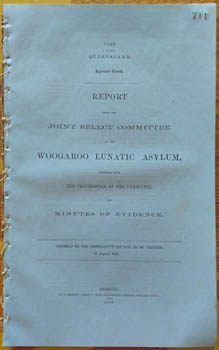

Woogaroo lunatic asylum. Report from the Joint Select Committee on the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum, together with the proceedings ... and minutes of evidence. Brisbane, Govt printer 1869. Foolscap disbound; [4],73pp and nine litho plates: plans and elevations. Au$450

Woogaro, Queensland's first lunatic asylum, was opened in 1865 and was a disaster: built in the wrong place, badly staffed, badly managed, with woefully inadequate buildings. Two inquiries were held in 1869, one by public servants and this one by a parliamentary committee. The focus here is on the buildings, the general plan and proper management. From this inquiry came the 1869 Lunacy Act. The committee recommend buildings on the "cottage" system and given the choice between plans by Tiffin and Suter - illustrated here - chose Suter's. He crammed twice the number of patients into each building at a saving of £18 per head.

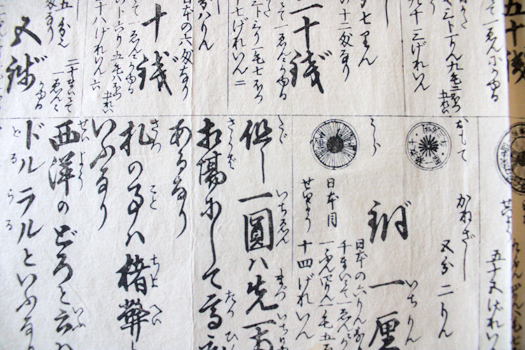

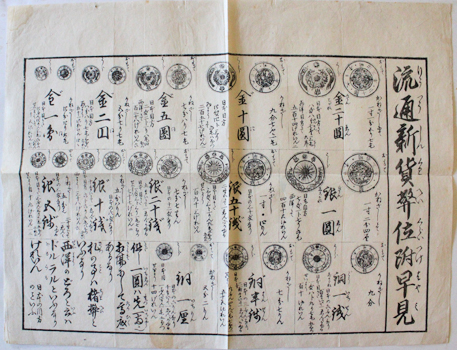

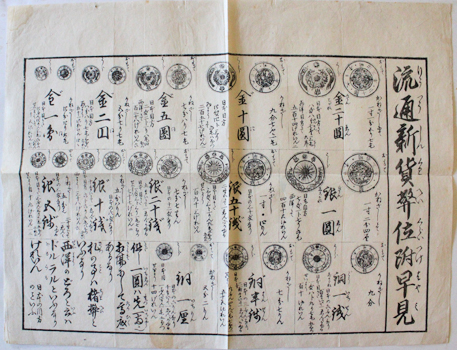

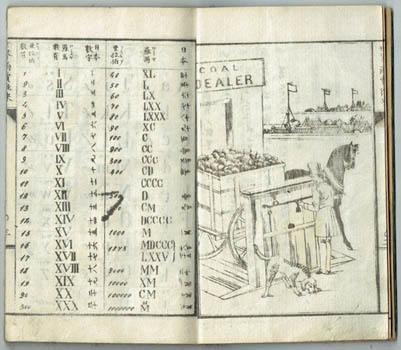

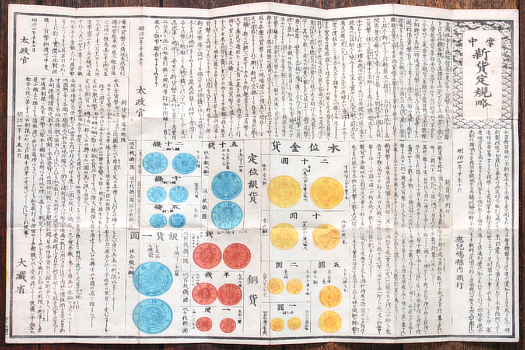

Kawaraban. [Ryutsu Shin Kahei-i-tsuki Hayami]. n.p.n.d. [c1870]. 32x41cm wood cut. A couple of small blotches, rather good. Au$165

A quick guide to the new coins in circulation. Added to the mass of new things for Japanese to learn and new ways of thinking, with the Meiji restoration, was the new yen based currency.

Kawaraban - illicit illustrated news sheets for the streets - were produced by the million for a couple of hundred years so of course few survive. They were produced for anything more interesting than the drop of a hat.

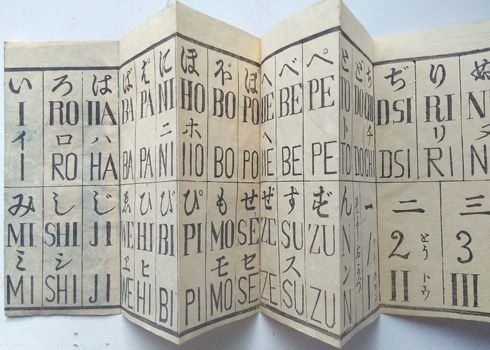

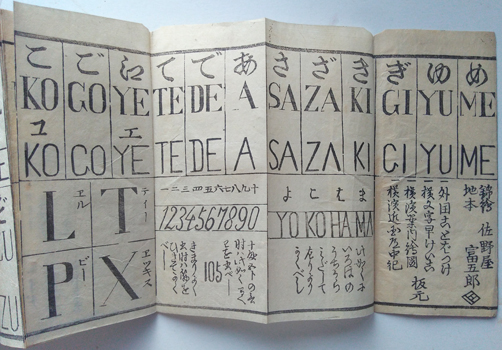

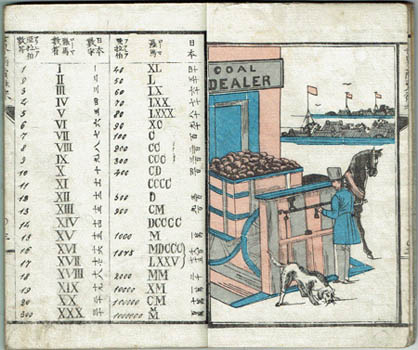

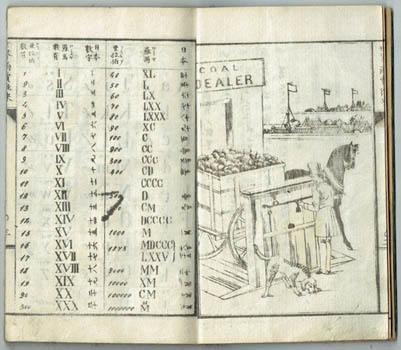

- [Yokomoji Iroha - Haya Keiko]. Yokohama? Sanoya Tomigoro [c1870?]. Woodcut on four joined sheets that folds from 15x7cm out to 130cm. Decorated title panel printed in blue and black, last blank panel with several small red stamps reading Naga ( ) and one Nagata ( ). An outstanding copy of something pretty well guaranteed not to survive second or third uses. Au$600

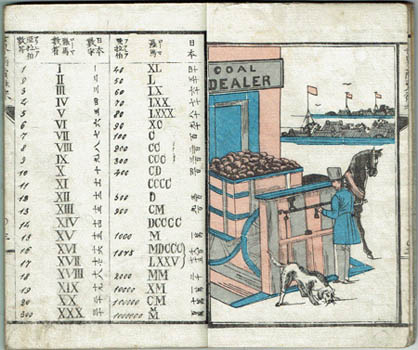

A captivating pocket or sleeve guide to horizontal writing with some numbers thrown in - Roman numerals for reading clocks - the latest of what must have seemed an endless array of challenges to life in Meiji Japan. Iroha might be translated into English as ABC.

Sanoya Tomigiri was a print publisher who moved from Tokyo (Edo) to Yokohama when it opened to the west and where he also became a singer. He is known as the publisher of prints by Yoshitoshi and at least four of the Utagawas, maps, guides and handy educational things like this.

I found a reference to something with almost this title printed by him at the beginning of the Meiji but it isn't the same thing, not even close. There may be another copy of this somewhere but I haven't found it.

SWINBURNE, Algernon Charles. Ode on the Proclamation of the French Republic. September 4th, 1870. London, Ellis 1870. Octavo publisher's printed wrapper; 24pp. A few minor signs of use but a pretty good copy. Au$100

First edition of Swinburne's tormented and fairly blood-thirsty paean to the Republic.

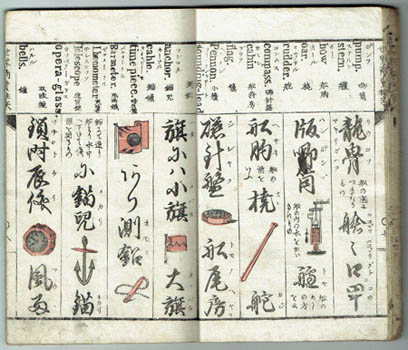

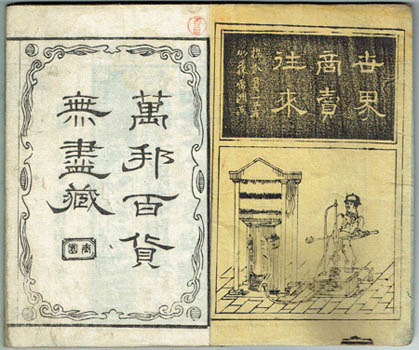

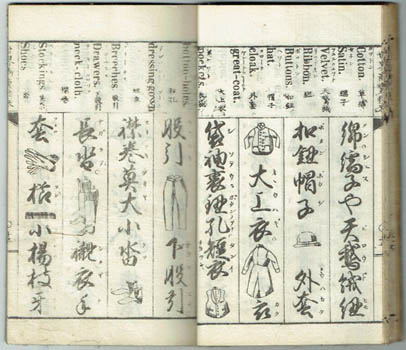

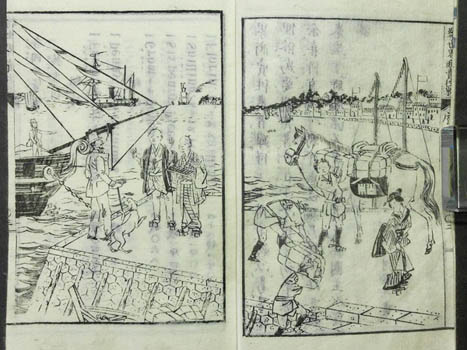

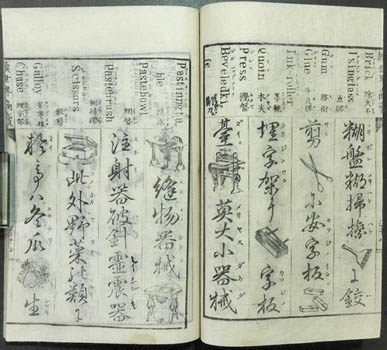

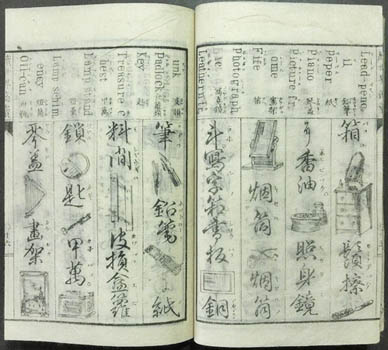

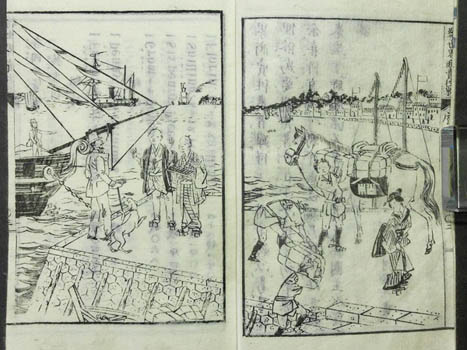

Hashizume Kan'ichi. [Sekai Shobai Orai - literally World Trade Traffic]. Tokyo 1871? 180x120mm publisher's wrapper (title label with a small chip); 26 double folded leaves; one full page colour and numerous small colour illustrations throughout, a half-page plain illustration inside the front cover. Clearly a read copy, with some small blotches and smudges but still rather good. Au$750

First edition it seems of this delightful and handy bilingual vocabulary of world trade giving the English, with Japanese explanations, of a wide range of terms, place names, goods, and so on. I've seen a couple of copies of the second edition, 1873, not in colour. Neither can I find a record of a colour copy of any edition. Waseda University illustrates a copy of the 1871 edition with the half page illustration inside the front cover in colour but not anything else. Clearly even workaday Japanese books like this can be intricate enough to please any French bibliophile.

Hashizume, who specialised in handbooks on trade and on foreign languages, produced, I think, three of these guides for merchants with similar titles. This is the first and the next two supplement this.

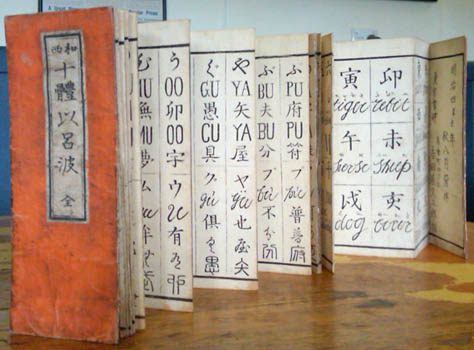

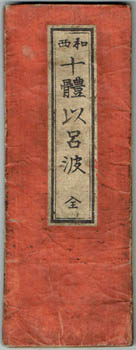

[Wasei Jutai Iroha]. Tokyo, Yoshidaya Bunzaburo 1871 [Meiji 4]. 165x63mm, publisher's wrapper with title label (rumpled and forgivably grubby); 30pp accordian folding. Used but a more than decent copy. Au$475

A nifty little pocket or sleeve book - that opens right to left like western books - teaching how to write English letters but not in English. This teaches how to write Japanese phonetically with the English or romanised alphabet - what was to become romaji. The Portugese missionaries had formulated a romanised system so that missionaries could instruct their Japanese victims without having to learn how to read Japanese but once they were tossed out of Japan such a system was quickly forgotten. It was only with the Meiji restoration and orders from the top that modernisation must follow that making Japanese intelligible to westerners became a desirable skill. At the end are numbers, the twelve animals of the zodiac - more or less, unfamiliar characters and spelling defeated the writer or block cutter on a few - and the seasons and points of the compass.

This seems rare, both in and outside Japan. OCLC finds no copies and my searches of Japanese libraries finds only one copy - in the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

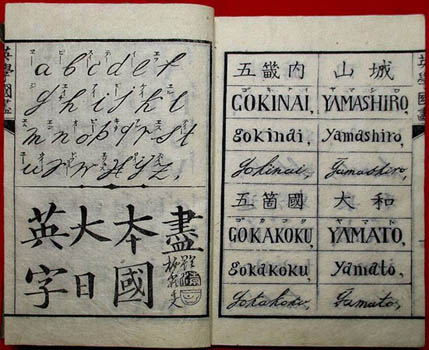

Hashizume Kan'ichi. [Dai Nihon Kunizukushi - Eiji Santai]. Tokyo, Wan'ya Keihe 1871 [Meiji 4]. 18x13cm publisher's wrapper (a bit used, label missing); 36pp on 18 double folded leaves; opening right to left. Au$300

A writing guide teaching how to read and write the English alphabet in its three guises but not in English. One of the earlier attempts at formulating what is now Romaji; Hashizume here standardizes Japanese place names into phonetic transliteration. The Portugese missionaries had formulated a romanised system so that missionaries could instruct their Japanese victims without having to learn how to read Japanese but once they were tossed out of Japan such a system was quickly forgotten. It was only with the Meiji restoration and orders from the top that modernisation must follow that making Japanese intelligible to westerners became a desirable skill. Worldcat finds a couple of copies in Japan, none outside.

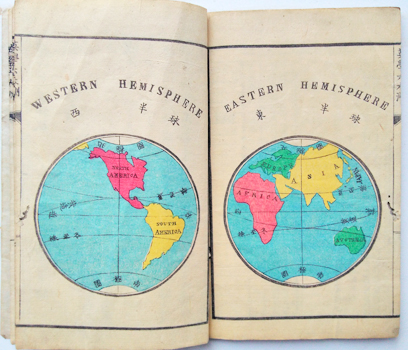

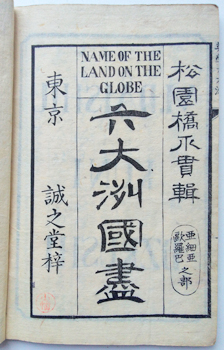

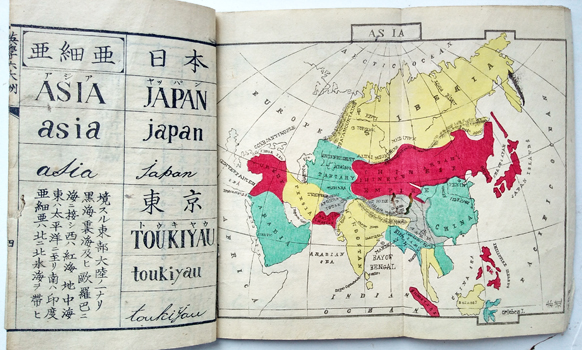

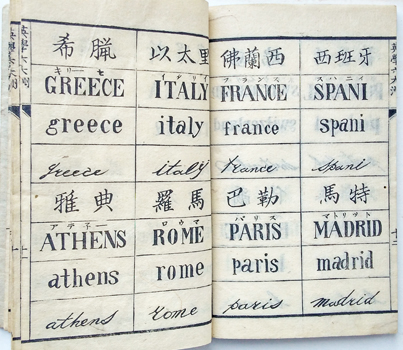

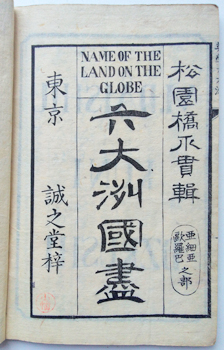

Hashizume Kan'ichi. [Rokudaishu Kuni Zukushi] Name of the Land on the Globe. VI. Daishiu Kuni Dzkushi [sic]. Tokyo, Wan'ya Kehei 1871 (Meiji 4). 18x13cm publisher's wrapper with title label (covers mottled); [32]pp, doubled page colour world map in two hemispheres and two folding colour maps (Asia and Europe). A touch of worming, pretty insignificant; quite a good copy. Au$350

Just when I thought I must have seen all of Hashizume's handy little guides to English, up pops another. This guide to place names in the three forms: upper, lower case and long hand, is titled as complete but, as this covers Asia and Europe, now I have to look for a companion volume for the rest of the world.

Hashizume, the translator, produced quantities of handy guides to English and useful translations, most of which are idiosyncratic in their choices of what is considered essential to any Japanese setting out to work in English.

Worldcat finds only the NDL entry.

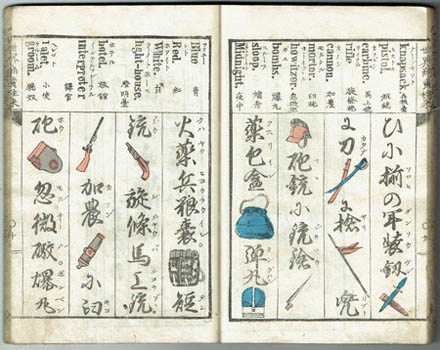

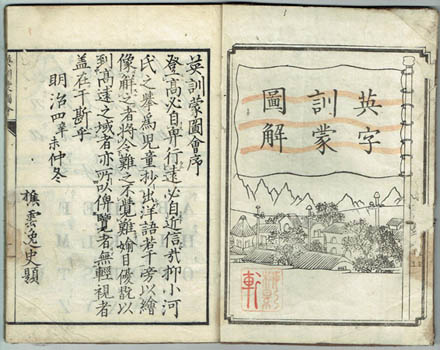

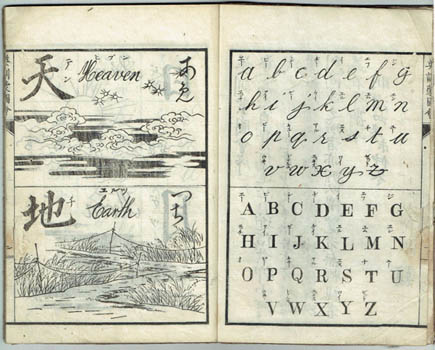

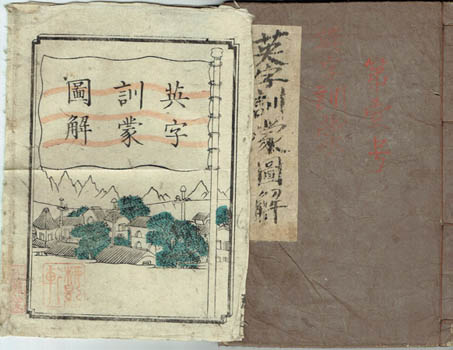

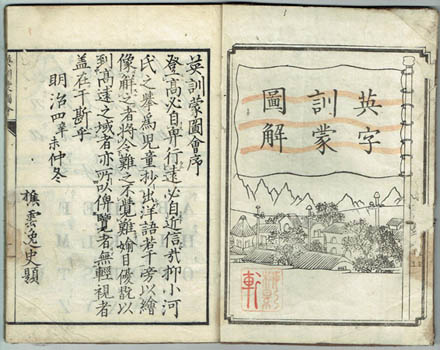

[Eiji Kunmo Zukai or Ei Kuno Zukai depending on the transcriber]. Kyoto, Ogawa Kinsuke 1871 (Meiji 4). 225x155mm publisher's wrapper with title label; woodblock illustrations throughout. Some worming and a marginal stain, neat repairs to the first few margins. A very decent copy with its colour illustrated outer wrapper, this smudged and rumpled but complete and untorn. Au$750

A rare and most appealing illustrated introduction to English. To an extent unseen in any other non-western culture faced with the colonial ambitions of the west the Japanese controlled their own re-education. They were not showered with unwanted primers by missionaries and other pious businessmen. They produced, printed and determinedly digested their own, using whatever sources they could find, the occasional hired expert and their imagination.

The more I look at books like these, which were assiduously studied, the more I wonder how anyone learnt any English. How many Japanese went to their graves calling a camera a desk and hoping for an opportunity to introduce 'pluckant' into conversation? Leaving aside errors, books like these make no sense as tools to me but tens, hundreds of thousands of Japanese students set out with these as guides on the road of bunmei kaika - government sponsored enlightenment and civilization - and got there way faster than anyone should have. In fact the more I think about it the more I wonder how anyone learns any language.

Hashizume Kan'ichi. [Sekai Shobai Orai - literally World Trade Traffic]. Tokyo, Seikichi 1871 [Meiji 4]. 180x120mm publisher's wrapper (a bit rumpled); 26 double folded leaves; one full page and numerous small illustrations throughout. Title page on yellow with a man operating some mysterious, to me, mechanism. Au$200

First edition of this handy bilingual vocabulary of world trade giving the English, with Japanese explanations, of a wide range of terms, quantities, goods, professions, and so on. I used to think the bibliography of Hashizume's handbooks on foreign trade was straightforward: three, this, the first in 1871 following it up with two more in 1873. Since then I've discovered variants and variants of variants. There are some of the expected amusing errors in spelling and typography but far fewer than in the later books.

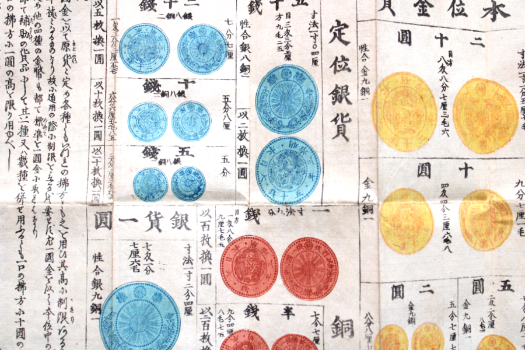

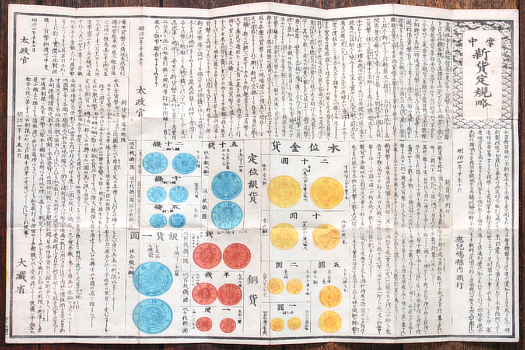

: [Shochu : Shinka Jogi Ryaku]. Kagoshima Prefecture, Dajokan 1871 (Meiji 4). 36x49cm folding into 12x6cm publisher's wrapper with title label (a bit grubby); woodcut illustrations of coins in colours. Rather good. Au$200

A palm size guide - until it's unfolded - to the new currency issued by the Ministry of Finance. Added to the mass of new things for Japanese to learn and new ways of thinking, with the Meiji restoration, was the new yen based currency. 1871 must have been a tough year for the slower thinking Japanese - I'm still hazy about metrification - and 1871 bought a new calendar, new system of time keeping, new currency, a new education system, new haircuts ...

I can only find mention of this in two provincial museums in Japan, nowhere else.

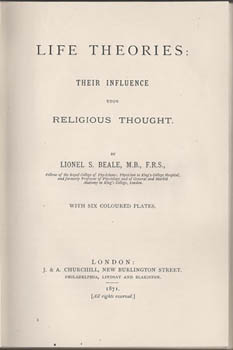

BEALE, Lionel S. Life Theories: their influence upon religious thought. London, Churchill 1871. Octavo publisher's brown cloth; xii,97,[2]pp and six coloured plates. Spotting of the endpapers but a nice, bright copy. Au$75

A good example of the weight of authority arrayed against wrong-headed fashion. Beale was no lightweight in the medical establishment and Churchill were authoritive publishers of medical books. Beale stood firm against the germ theory and here he stands firm against physical theories of nature. The coloured plates are from microscope studies - which Beale is possibly now best known for - evidence that this is no mere theological argument.

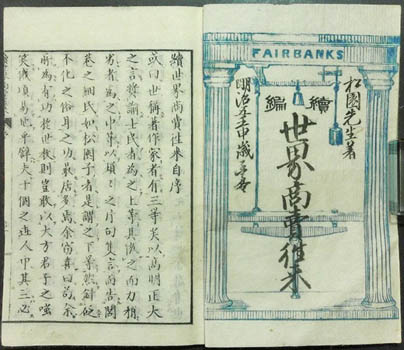

Hashizume Kan'ichi. [Zokuhen Sekai Shobai Orai]. Tokyo, Gankinya Seikichi 1872 (Meiji 5). 180x120mm publisher's wrapper without title label (cover marked); 26 double folded leaves; one double page illustration and several small illustrations through the text, title page framed in blue Fairbanks standing scales. Mildly used. Au$350

First edition I think of this handy bilingual vocabulary of world trade giving the English, with Japanese explanations, of a wide range of terms, quantities, goods, professions, and so on. I used to think the bibliography of Hashizume's handbooks on foreign trade was straightforward - three, the first in 1871 following it up with two more in 1873. Since then I've discovered variants and variants of variants.

This book isn't 'Zokuzoku Sekai Shobai Orai' as I first thought. The contents are completely different. Zokuzoku begins with foreign measures of quantity, this begins with foreign currencies. Like that the English text has been cut in wood, it isn't type. There are some endearing spelling mistakes, mishapen or reversed letters and odd truncations - fewer than in the later book - but more puzzling than these are some of the chosen terms for Japanese traders to learn. The tools of trade for printers and binders are included, which makes sense - as do fruit and vegetables - but how many merchants dealt in camels and leopards?

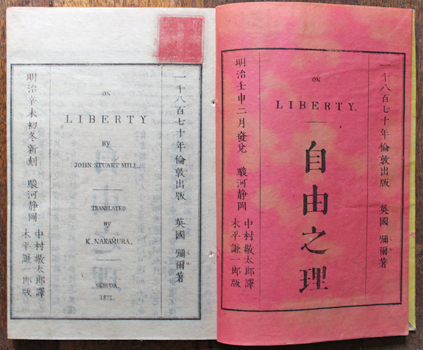

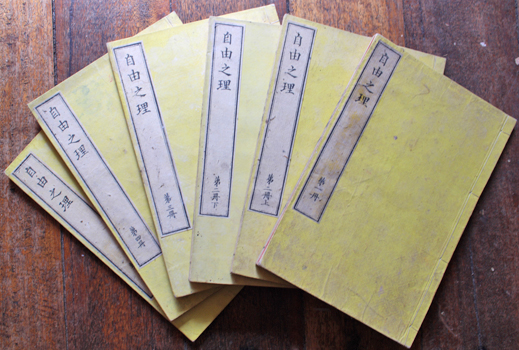

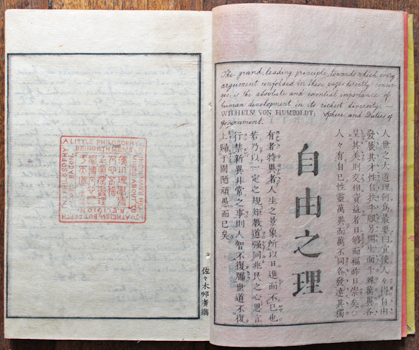

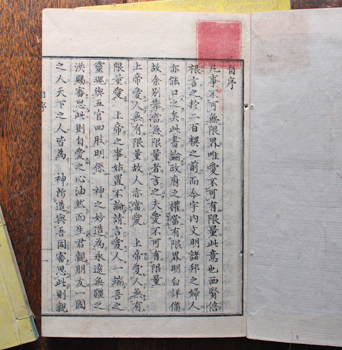

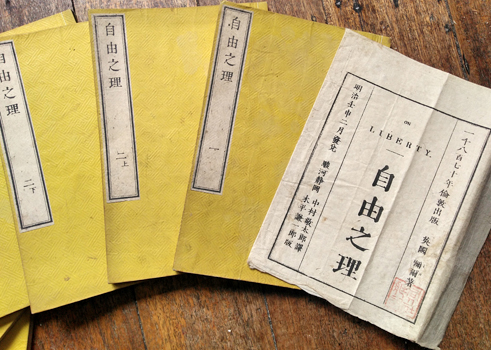

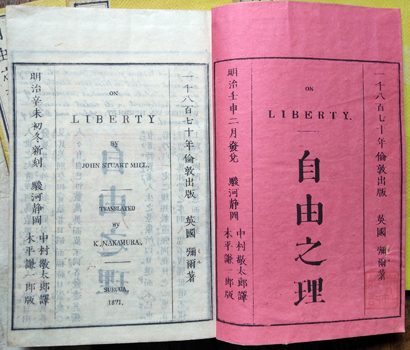

Mill, John Stuart and Nakamura Masanao. [Jiyu no Ri or Jiyuno Kotowari depending on the transcriber]. On Liberty. Shizuoka, Kihira Ken'ichiro [1872]. Five volumes in six books 23x16cm, publisher's yellow wrappers with title labels. Preface in English signed EWC, this was Edward Warren Clark who taught science in Shizuoka and, later, Tokyo. A square red stamp in the top corner of the first page of each volume with faint signs of characters, no other signs of ownership. A rather good set. Au$1500

The first Japanese edition of Mill's On Liberty - a book that Douglas Howland (in Personal Liberty and Public Good) tells us was "reportedly read by the entire generation of educated Japanese who came of age during the restoration".

I hoped to be able to nail down any issue points and clear up any confusion between the two forms this book takes: the five volumes bound as six books, as here, with volume two divided into two; or bound as five books. The confusion is heightened because many libraries and cataloguers use the 1871 date on the title, ignoring the preface dated January 1872.

I thought that a sort of colophon for Dojinsha - Nakamura's school - pasted inside the last back cover might help, but that leaf appears in both versions. Only the cover labels seem to be different. I've found nothing in any language that examines the printing history and while the rule of thumb - everywhere in the world - is that the more costly version - in materials and time - usually came first, I've had to conclude that there isn't any discernible priority and the difference may well be where, rather than when, the books were bound.

Nakamura's translation of Smile's 'Self Help' was also published by Kihira in Shizuoka and it seems that Kihira Ken'ichiro existed as a publisher only for Nakamura's translations of these two books which he made in Shizuoka - home of the deposed Tokugawa shogun - where he taught after his return from England in 1868 until 1872. In other words, Nakamura was really the publisher of both books.

Worldcat finds five, maybe six, locations outside of Japan - one in Britain, the rest in the US - all but one are catalogued as 1871.

It's by the way but I found this while reading up on something else: "Nakamura Masanao ... contributed a vitriolic piece on the sins of the novel to the first issue of Tokyj shinpo in 1876. He insisted that novels caused epidemics and violated the sanctity of marriage". (P.F. Kornicki; Disraeli and the Meiji Novel).

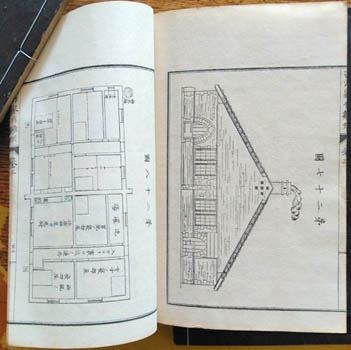

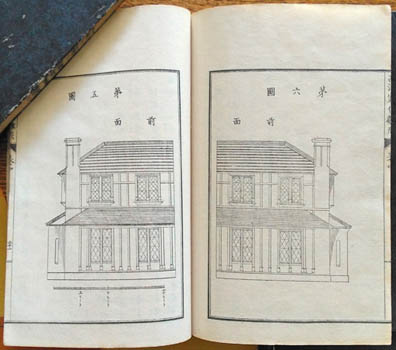

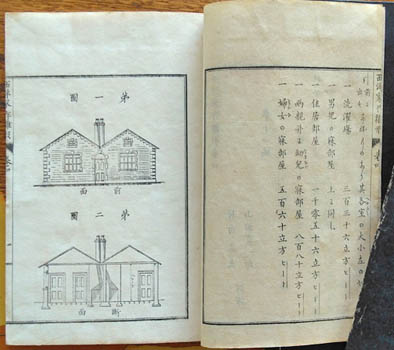

ALLEN, Charles Bruce; Murata Fumio & Yamada Koichiro. [Seiyo Kasaku Hinagata]. Tokyo, Gyokuzando 1872 (Meiji 5). Four volumes 23x15cm publisher's wrappers with printed title labels. Illustrations through the text and full page plates - copper engravings. Labels rubbed and mildly chipped; a rather good copy. Au$1500

The first western architecture book published in Japan. I'm intrigued by the choice of the modest 'Cottage Building, or hints for improving the dwellings of the labouring classes' - one of Weale's utilitarian Rudimentary Treatises. Why not European grandeur? American mass production? Allen's small book first appeared in 1849-50 and remained in print, progressively updated, into the 20th century. This translation was made from the 1867, sixth edition.

A sensible enough choice I guess, but when has sense played any part in the introduction of new ideas? Murata Fumio edited 'Seiyo Bunkenroku' (1869 &c) - based on the reports of the Takenouchi mission of 1862 - which focused on England so the connection is clear enough. That there was any significant group pushing for philanthropic reform this early in the Meiji restoration comes as a surprise to me; perhaps this book was chosen as a slap in the face to the opponents of westernisation and modernisation. Ostensibly it was a response to the 1872 Tokyo fire. Allen's book was given by an Englishman to the translator as useful for information on fire-proof buildings. Could it be that simple?

Worldcat finds no copy outside Japan - Columbia apparently has a later reprint. A search of the specialist libraries I can think of found no more.

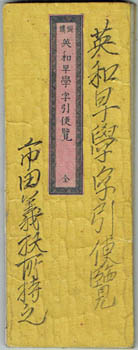

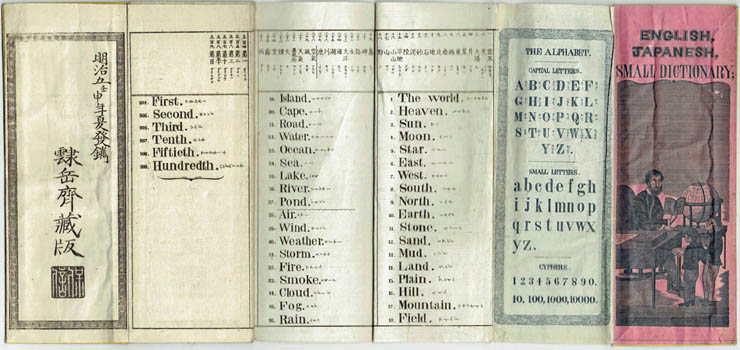

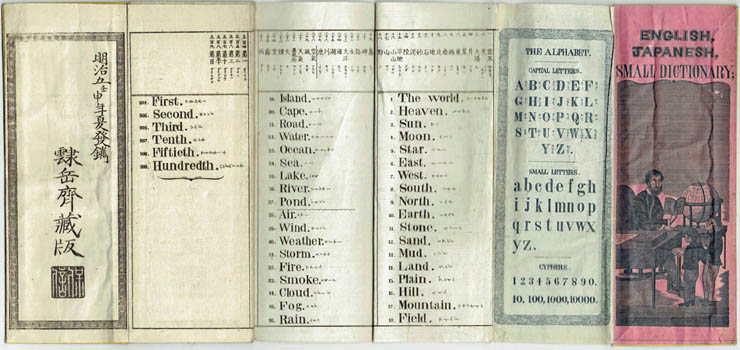

English, Japanesh, Small Dictionary; [Eiwa haya-gaku jibiki Binran]. Tokyo, Osaka? 1872 (Meiji 5). 16x6cm publisher's wrapper with title label; illustrated title in English on red paper, 30pp accordian folding, first page printed in blue. Owner's inscriptions on the covers. A pleasing copy, a most pleasing book. Au$300

Perfect for the narrowest pocket, or sleeve maybe. The explanatory Japanese with each of the 509 entries is tiny and clear. Osaka Women's University has a copy and that's all I could find anywhere. The NDL database lists it only on microfilm as part of a collection of English studies titles issued in the seventies.

Mill, John Stuart and Nakamura Masanao. [Jiyu no Ri or Jiyuno Kotowari depending on the transcriber]. On Liberty. Shizuoka, Kihira Ken'ichiro [1872]. Five volumes in six books 23x16cm, publisher's yellow wrappers with title labels. Preface in English signed EWC, this was Edward Warren Clark who taught science in Shizuoka and, later, Tokyo. Covers a bit marked, an excellent set with the original printed outer wrapper (fukuro). Au$2500

The first Japanese edition of Mill's On Liberty - a book that Douglas Howland (in Personal Liberty and Public Good) tells us was "reportedly read by the entire generation of educated Japanese who came of age during the restoration".

I hoped to be able to nail down any issue points and clear up any confusion between the two forms this book takes: the five volumes bound as six books, as here, with volume two divided into two; or bound as five books. The confusion is heightened because many libraries and cataloguers use the 1871 date on the title, ignoring the preface dated January 1872.

I thought that a sort of colophon for Dojinsha - Nakamura's school - pasted inside the last back cover might help, but that leaf appears in both versions. Only the cover labels seem to be different. I've found nothing in any language that examines the printing history and while the rule of thumb - everywhere in the world - is that the more costly version - in materials and time - usually came first, I've had to conclude that there isn't any discernible priority and the difference may well be where, rather than when, the books were bound.

Nakamura's translation of Smile's 'Self Help' was also published by Kihira in Shizuoka and it seems that Kihira Ken'ichiro existed as a publisher only for Nakamura's translations of these two books which he made in Shizuoka - home of the deposed Tokugawa shogun - where he taught after his return from England in 1868 until 1872. In other words, Nakamura was really the publisher of both books.

Worldcat finds five, maybe six, locations outside of Japan - one in Britain, the rest in the US - all but one are catalogued as 1871.

It's by the way but I found this while reading up on something else: "Nakamura Masanao ... contributed a vitriolic piece on the sins of the novel to the first issue of Tokyj shinpo in 1876. He insisted that novels caused epidemics and violated the sanctity of marriage". (P.F. Kornicki; Disraeli and the Meiji Novel).

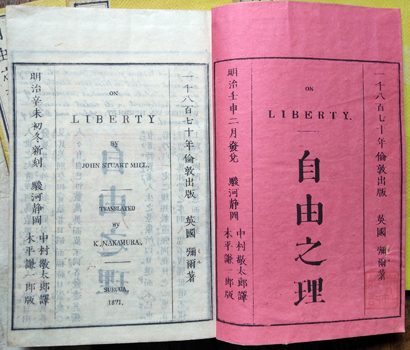

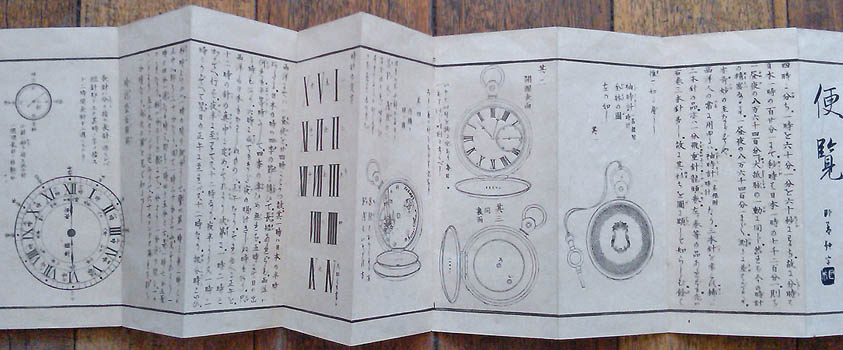

Yanagawa Shunsan. [Seiyo Tokei Benran]. Tokyo, Yamatoya Kihee 1872 [Meiji 5]. 185x80mm publisher's stiff wrapper with title label (quite marked), accordian folding to form 34pp with woodblock illustrations throughout. A nice copy. Au$500

An introduction to the western watch and its workings and - more important - western time and how to tell it. Roman numerals and the hour, minute and seconds hands are explained and a series of watch faces guide us through the rest of the intricacies of measuring time in the western style. Obviously for the pocket, this could be hauled out with the new gizmo when its fledgling owner was stumped. Or even by a non-watch owner faced with a public clock. At the end the thermometer is illustrated and explained too.

This is not to say that the Japanese hadn't already mastered the clock. Since the Jesuits introduced clocks in the 16th century Japanese clockmakers had developed complex weight and spring driven mechanisms to run timekeepers according to the unequal hours of day and night, varying according to season. But in 1872 the government switched from the lunar calendar to the solar calendar and abolished traditional timekeeping and a whole nation had to start again from scratch.

Makes sense to me that daylight hours are longer and night hours shorter in summer and the reverse in winter. We all know that despite what the clock says all hours are not created equal. Bring back traditional Japanese timekeeping I say.

1 [2] 3 4 5 1 [2] 3 4 5   |