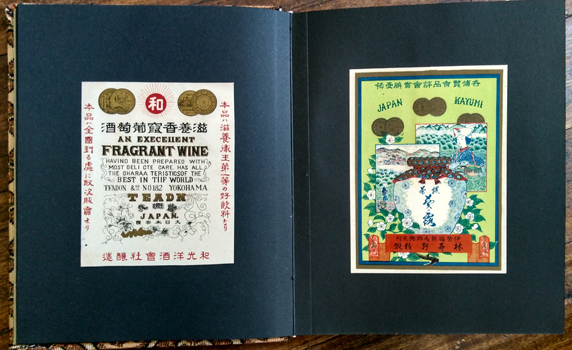

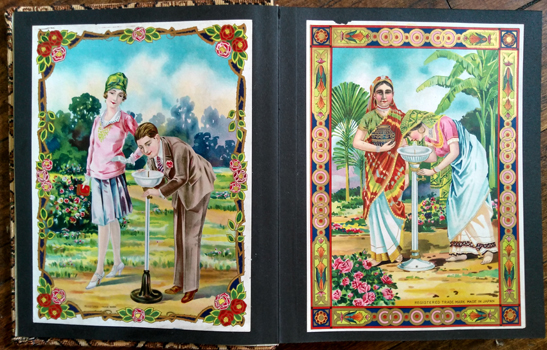

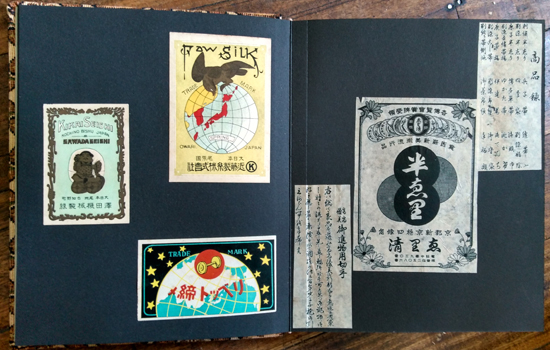

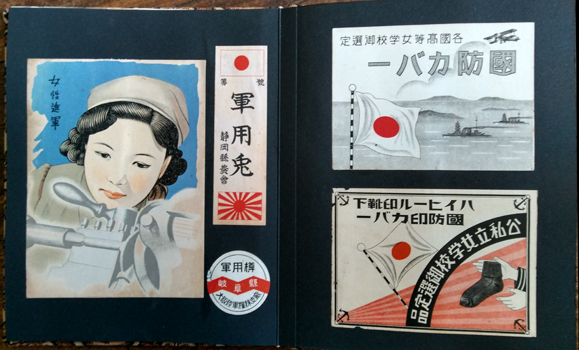

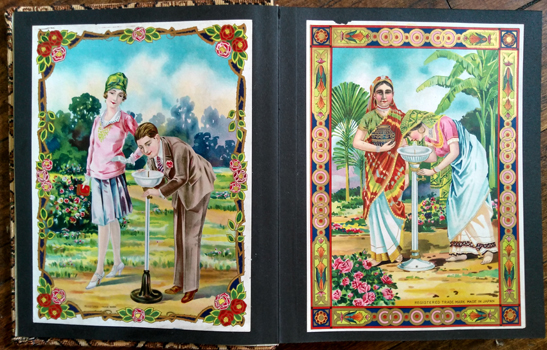

Advertising & trade marks. A Japanese album of labels, trade marks, etc. n.p. early to mid c20th. 29x24cm cross stitch cloth album with 73 examples mounted on 24 black card leaves. Collector's ex libris stamp with the name 'Nanbu' on the front endpaper. Au$400

A carefully collected and presented gathering of labels, wrappers and similar trade mark advertising ephemera - from translucent tissue to stiff card - dating from early in the century into the 1930s.

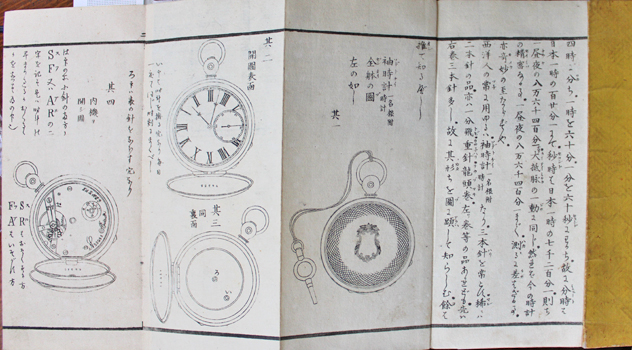

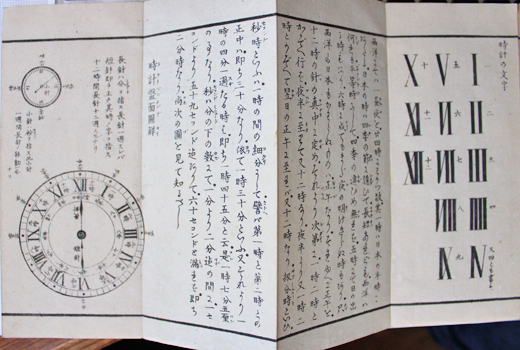

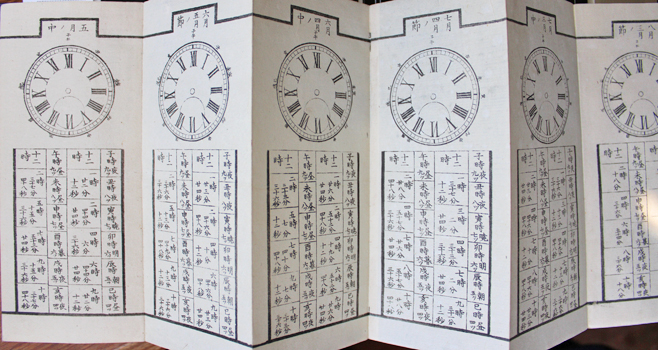

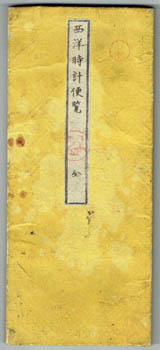

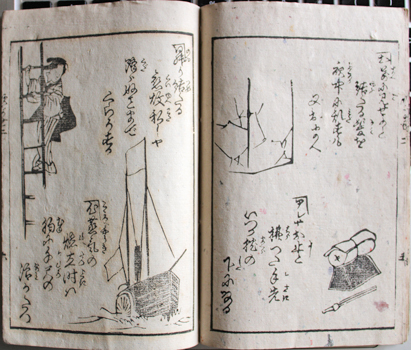

Yanagawa Shunsan. [Seiyo Tokei Benran]. Tokyo, Yamatoya Kihee 1872 [Meiji 5]. 185x80mm publisher's stiff wrapper with title label (marked), accordian folding to form 34pp with woodblock illustrations throughout. Rather good. Au$500

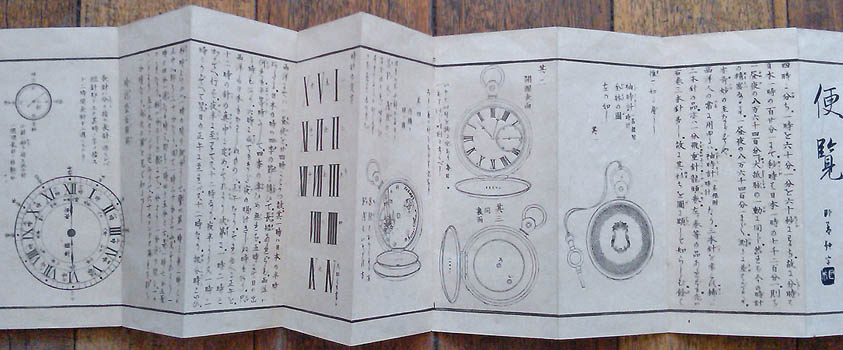

An introduction to the western watch and its workings and - more important - western time and how to tell it. Roman numerals and the hour, minute and seconds hands are explained and a series of watch faces guide us through the rest of the intricacies of measuring time in the western style. Obviously for the sleeve or pocket, this could be hauled out with the new gizmo when its fledgling owner was stumped. Or even by a non-watch owner faced with a public clock. At the end the thermometer is illustrated and explained too.

This is not to say that the Japanese hadn't already mastered the clock. Since the Jesuits introduced clocks in the 16th century Japanese clockmakers had developed complex weight and spring driven mechanisms to run timekeepers according to the unequal hours of day and night, varying according to season. But in 1872 the government switched from the lunar calendar to the solar calendar and abolished traditional timekeeping and a whole nation had to start again from scratch.

Makes sense to me that daylight hours are longer and night hours shorter in summer and the reverse in winter. We all know that despite what the clock says all hours are not created equal. Bring back traditional Japanese timekeeping I say.

Yanagawa Shunsan. [Seiyo Tokei Benran]. Tokyo, Yamatoya Kihee 1872 [Meiji 5]. 185x80mm publisher's stiff wrapper with title label (quite marked), accordian folding to form 34pp with woodblock illustrations throughout. A nice copy. Au$500

An introduction to the western watch and its workings and - more important - western time and how to tell it. Roman numerals and the hour, minute and seconds hands are explained and a series of watch faces guide us through the rest of the intricacies of measuring time in the western style. Obviously for the pocket, this could be hauled out with the new gizmo when its fledgling owner was stumped. Or even by a non-watch owner faced with a public clock. At the end the thermometer is illustrated and explained too.

This is not to say that the Japanese hadn't already mastered the clock. Since the Jesuits introduced clocks in the 16th century Japanese clockmakers had developed complex weight and spring driven mechanisms to run timekeepers according to the unequal hours of day and night, varying according to season. But in 1872 the government switched from the lunar calendar to the solar calendar and abolished traditional timekeeping and a whole nation had to start again from scratch.

Makes sense to me that daylight hours are longer and night hours shorter in summer and the reverse in winter. We all know that despite what the clock says all hours are not created equal. Bring back traditional Japanese timekeeping I say.

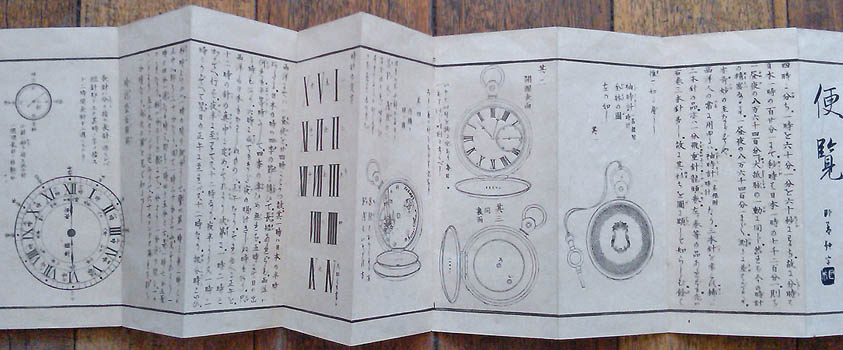

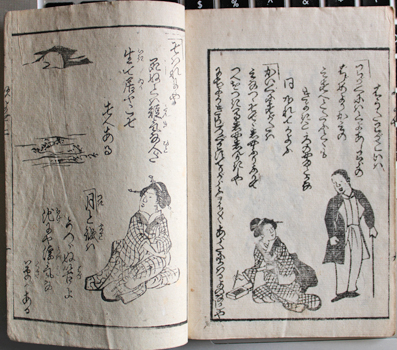

[Shinsen Shoka no Fukiyose]. n.p. n.d. [c1880?] 18x12cm publisher's colour woodcut wrapper; 10 double leaves (20pp); b/w woodcut illustrations throughout. Rather good. Au$125

A rare and charming songbook, apparently for children, which has a look of long tradition. But if these are proper shoka then it is a form of school song that began with Meiji reformation of education. The subjects are in any case thoroughly up to date: balloons, steamships and photographs.

None of these songbooks are going to be common. I found an entry for what might be the same book in the Ryukyu University catalogue; nothing else.

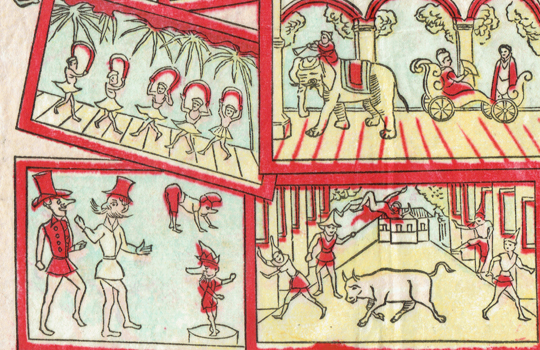

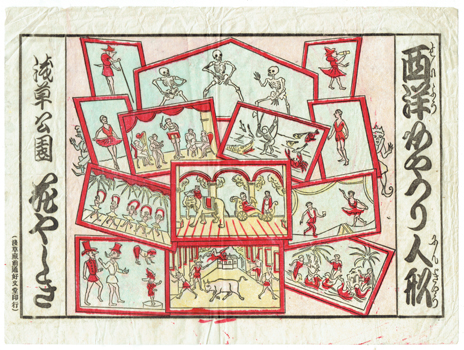

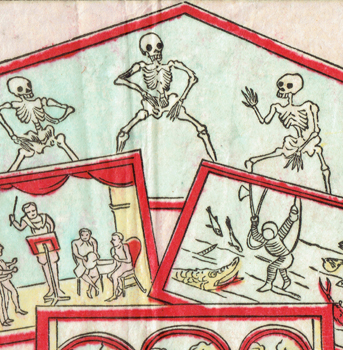

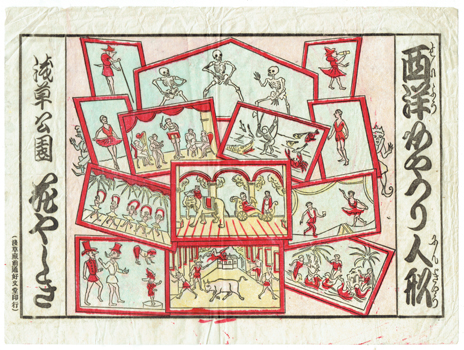

Puppets. [Seiyo Ayatsuri Ningyo]. Tokyo, Hanayashiki [188-?]. Woodcut on translucent paper with added colours, 25x19cm. Old fold, rumpled; rather good. Au$300

This hikifuda or flyer for the western puppet show in Asakusa Park's Hanyashiti - amusement park - exists in two forms: one with the main title across the top and the other in the right column, as here. The illustrations are the same. The Tokyo Museum has a copy of this and Waseda a copy of the other; I can't find one outside of Japan.

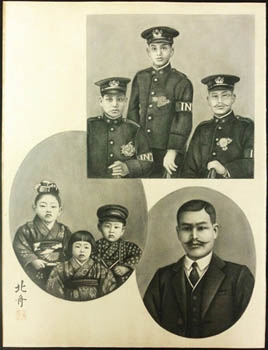

Photography - Japan. Portraits from photographs scrupulously hand painted to impersonate lithographs. n.p. [c1880-1890?]. Two sheets, 54x41cm and 60x48cm, with nine portraits all but one oval; each about 25cm - ten inches - high. Au$450

Are these the ultimate modern one-up-manship in family portraiture? Painted over photos are common enough and paintings from photos equally so but these are large scale, done from scratch purposely to mimic the grain of lithography. The stippling is so painstaking and exact that it would have been easier to make and print lithographs.

By the 1880's reaction to modernity and the west, by nationalists watching their tradition vanish, was strident and often powerful. Don't forget the western design of the residence of the new Imperial Palace was abandoned after earthquake damage to brickwork and the official carpenter took over. No small victory for superior Japanese traditions. The arguments over portraiture and photography are often unexpected, confusing and contradictory to me. Schools that I would think traditionalist welcomed the camera and realism - though some disliked photo portraits for moral or ethical reasons - but whatever the argument the photograph and its wedded industry - portraits painted in oils over or from photos - became ubiquitous essentials for the family shrine.

Our well to do family is not only on the side of western modernity, they go one step further by embracing the foreign technology of the lithographic print. So why hand painted on such a scale? Maybe partly because that's what a prominent family can afford but likely because portraits like this were still private family affairs. According to Conant (Challenging Past and Present), the painter Takahashi - portraitist of the Emperor - was thwarted in his 1880s project to paint portraits of the heroes of the Meiji by families refusing him use of their photographs.

The smaller set of portraits here is signed and sealed Hokushu. The other, clearly of later photos, has an illegible, to me, seal.

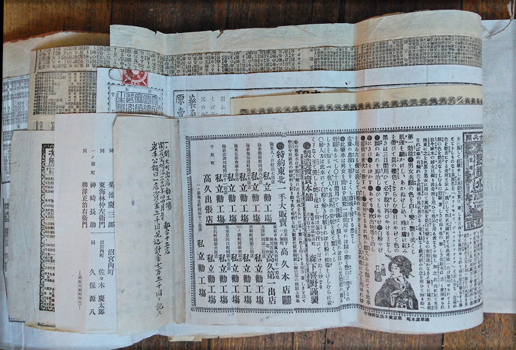

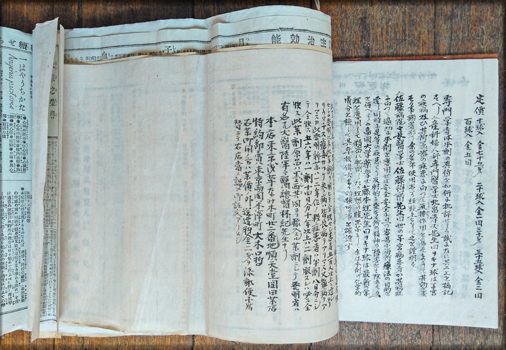

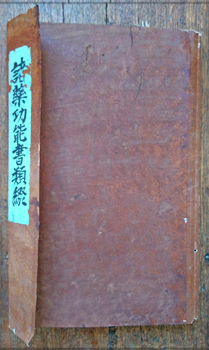

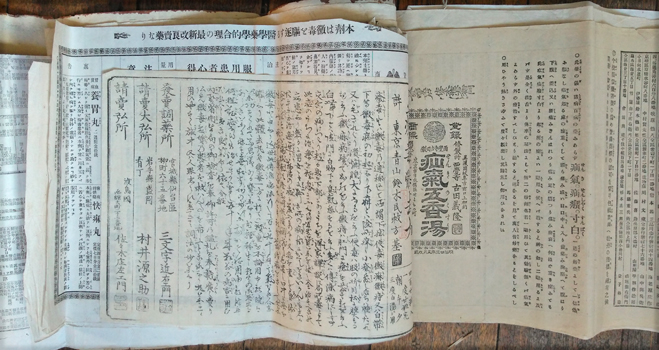

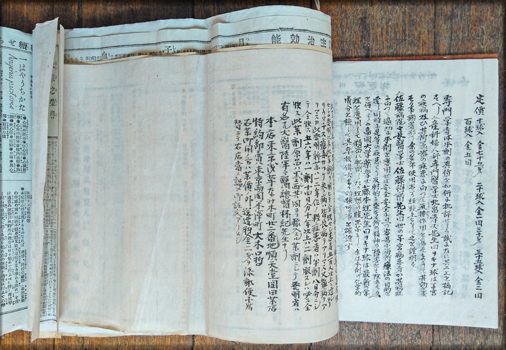

Patent remedies. [cover title]. A gathering of 19th century handbills or descriptive and instructive leaflets or wrappers for various patent, herbal or quack medicines. v.p. c1880 to c1900? 26 individual pieces bound to fold into a handmade board and stiff paper wallet style string tied binding, 28x18cm, treated with persimmon, hand lettered title piece. Some are quite large, some are printed on both sides and a few are woodcut. Au$1500

The work of the sort of collector who deserves a small shrine. Here have been carefully preserved the most disposable, awkwardly shaped and ephemeral records of a recondite corner in modern history: when drugs and cures became an industry.

At least one of these brands is still available: Chujoto for "Female Complaints" still alleviates menstrual pain. There may be others and I'll bet many are the foundations of current industrial giants. The only date I've spotted is Meiji 13 - 1880; Chujoto was apparently invented in 1893 (or by princess Chujo of the Fujiwara clan in a Snow White like tale) and some may be a little earlier or later.

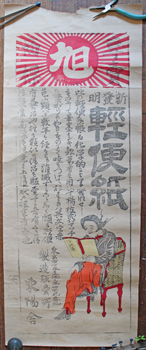

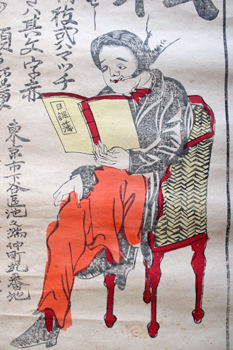

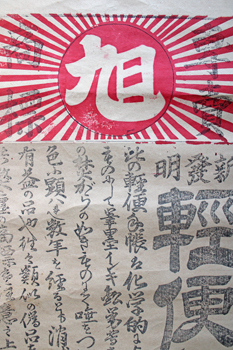

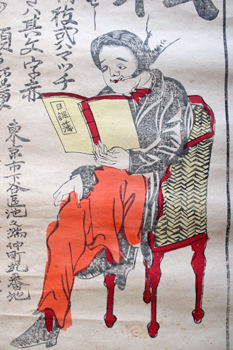

Paper. Toyosha? [Shin Hatsumei Keibenshi]. n.p. [Osaka?] [188-?]. 75x28cm woodcut with added colours. Piece from the top margin well away from the printing, a repaired tear; Quite good for a cheap, vulnerable bit of production. Au$150

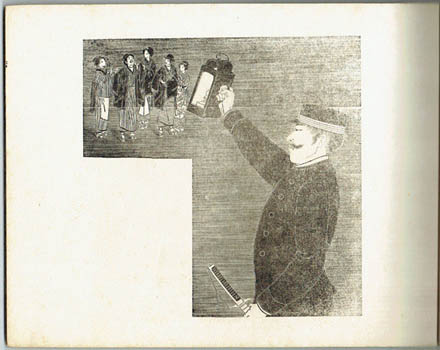

I believe this to be an announcement for a new invention of a lightweight paper. I hope not the paper this is printed on which seems heavy and coarse to me. Probably not considering the easy grasp of our newspaper addict. I suspect the cigarettes will stay on that side of his mouth until his left eye looks as sore as the right does now. Then he will switch back.

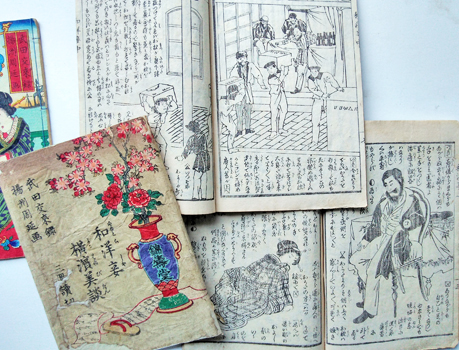

Takeda Korai. [Yamato Rasha Yokohama Bidan]. Tokyo? Kinjudo 1881 (Meiji 14). Three volumes 18x12cm, publisher's colour woodblock wrappers; 18 pages in each volume, illustrated by Chikanobu throughout with three frontispieces, a single page and a double page plate in colour in the first volume. Understandable thumbing but rather good with a laid down, chewed but mostly complete colour woodcut outer wrapper (fukuro). Au$1350

Slight maybe but there's a novel, or a play at least, just in those front covers. Yamato Rasha is, I'm told, a soap of women's lives with western men in Yokohama. Even I can tell, from the pictures, that they were lives filled with conflict, devious schemes, jealousy, violence by footwear ... busy indeed.

There is a modern reprint but I find only one entry in worldcat for the original outside Japan.

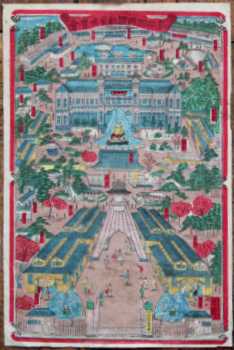

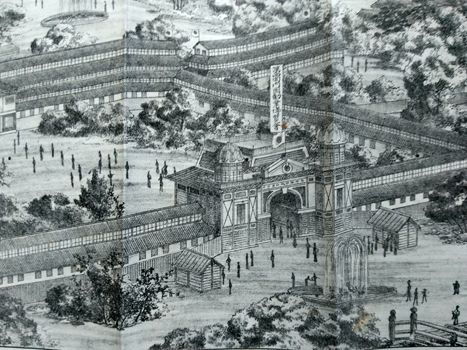

Exhibition - Tokyo 1881. Utagawa Kunitoshi. [Dai Nikai Naikoku Kangyo Hakurankai]. Tokyo, Shimizu Kahei 1881 (Meiji 14). 38x26cm colour woodcut (a bit rumpled). Au$300

A useful birds-eye view of the second national industrial exhibition, held in Ueno Park in 1881. It, despite hard times, quadrupled in size and almost doubled the attendance of the first, 1877, exhibition. Centre stage is the clock tower by Kaneda Ichibei.

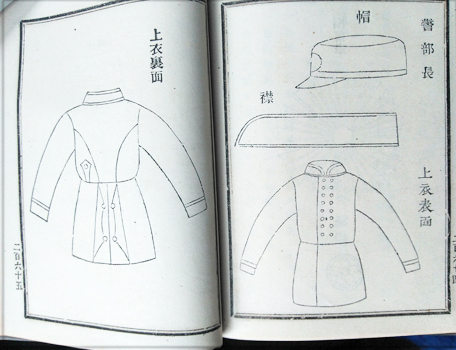

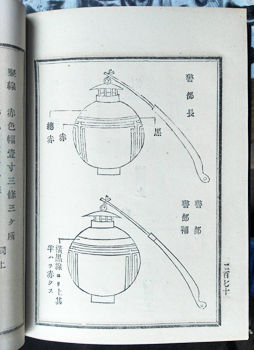

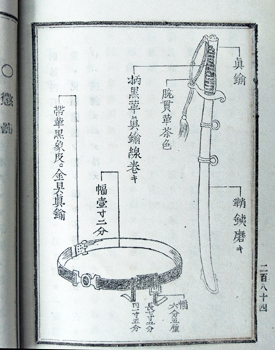

Police. Murakami Yoshitomo. : [Genko Hoki : Junsa Kokoroe]. Osaka, Bunkeido 1883 (Meiji 16). 15x11cm publisher's cloth; 286pp, line illustrations of uniforms and equipment. A tear in one leaf; a rather good copy. Au$200

A charming little book in its quiet way, this is a complete handbook with everything a police officer needs to know. Worldcat finds only the NDL entry.

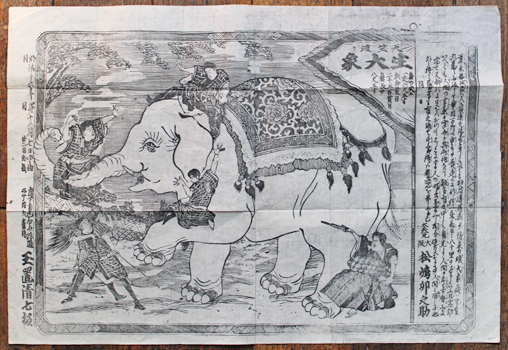

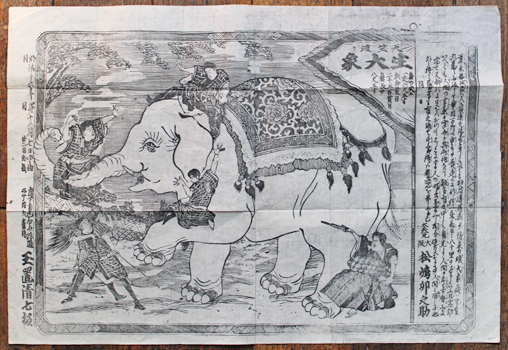

Elephant advertisement. : [Tenjiku Watari : Nama Daizo]. Osaka, Tamaki Seishichi 1883 (Meiji 16) Woodcut broadside 37x55cm. Rather good. Au$650

A kawaraban style advertisement for the great elephant show and a higher class - and grander - bit of art than the ones produced in Yokohama that I've seen, one dated 1875 and one 1883.

1863 was the year of the elephant in Japan, the great Indian elephant drew squillions of spectators and artists and printmakers went crazy. It wasn't the first elephant to arrive in Japan but it had been near 150 years since the last one. Apparently Raffles sent one in 1808 as a deal sweetener but it was refused and expelled - with a hundred bales of wheat from the shogun for the return journey. Just as well, while elephants had been celebrated in art for centuries, elephants in person didn't have long happy lives in Japan.

The 1863 elephant went on tour after a spell in Tokyo but is our elephant the same one? Is it the same elephant who starred in Yokohama which, according to the unreliable and incongruent ages given on different prints, was too young? Certainly our elephant has progressed from being a drawcard by merely existing to being the star of a theatrical show.

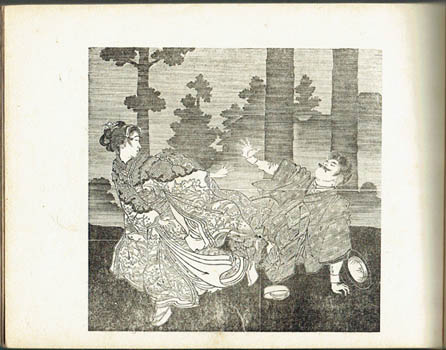

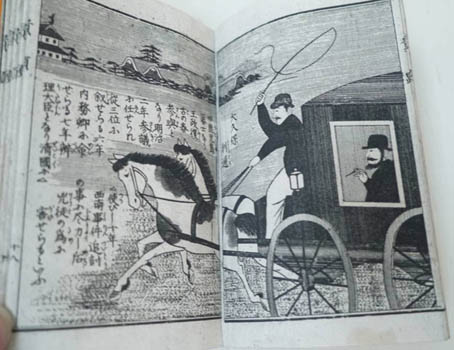

Dokufu. Hanai Oume? Set of proof wood engraved illustrations for a Japanese serial story. n.p. n.d. [c 1887?] 19x26cm, contemporary plain wrapper; 41 wood engravings on 21 double folded leaves. A little browning. Au$475

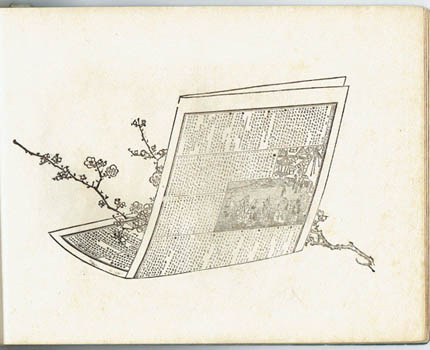

A prime example of the strange casserole of Meiji Japan. In form, in technique, in content and in production these hold all the paradoxes of Japan embracing western modernisation while hanging fast to tradition. These are the illustrations for what seems a rollicking sword and sash thriller but ... it is set in a modern metropolis; bowler hats, suits and dashing mustachios are not out of place, neither is what looks like a railway station. And these are not ukiyo-e woodcuts for a popular novel, these are western wood engravings for a long serial - there are 41 after all - in a newspaper or broadsheet magazine; an illustration of such a paper helpfully holds a bough of blossoms in one illustration. The subject apart, the glaring difference between these and any western illustrations is the skill of artist and engraver, all but a few western counterparts are put to shame.

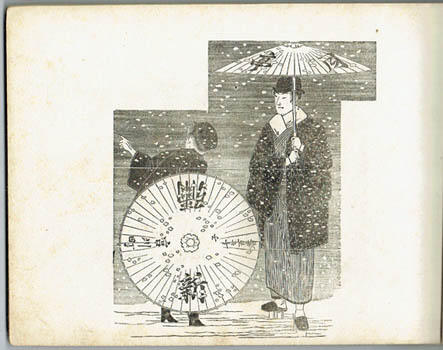

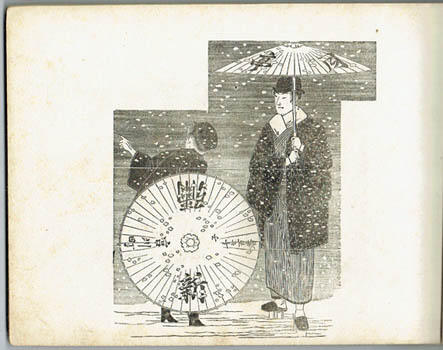

I'm convinced that these relate to Hanai Oume the celebrated Tokyo geisha-teahouse owner who, in 1887, stabbed her employee who, apparently in concert with her father, was trying to muscle her out of the business. The first illustration here shows two men holding umbrellas that, I'm told, advertise a restaurant or 'licenced pleasure quarter' remarkably similar to hers: Suigetsu. The umbrella was part of her claim of self defence: Minekichi attacked her with the knife, she disarmed him with her umbrella and then stabbed him.

Oume or O-ume - her professional name - was celebrity manifest, one of the three most famous dokufu (poisonous women) of the Meiji. Her murder trial was public and though crowds unable to get in became irate every moment was covered in the press; books were published within minutes, kabuki plays and novels performed and published, and the newspapers made rich. Yoshitoshi produced a famous print of the murder as a supplement for the Yamato Shimbun but while there is plenty of violence in these pictures there is no murder. Spin-off or fanciful concoction, there's a good story here.

There is an owner's (maybe artist's?) seal which I make out to be 春耕慢虫 - I'm sure I'm wrong.

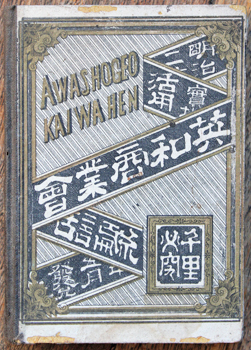

Makino Yasuzo. [Eiwa Shogyo Kaiwahen] Awashogeo Kai Wa Hen [cover title]. Kyoto, Makino Yasuzo 1887 (Meiji 20). 13x9cm publisher's cloth backed decorated boards (some surface nibbling); [4],60pp on double folded leaves. Signs of use but rather good for such a flimsy binding and vulnerable book. Au$150

Here's another of these nifty little bi-lingual conversation books; this one designed to baffle business people. I don't know how the Japanese version reads but it's a foolhardy customer who says to me, "Please charge these to my credit; I will pay you when it is convenient." I've had many customers who think that but they don't say it out loud. Not any more.

Worldcat finds no copies outside Japan.

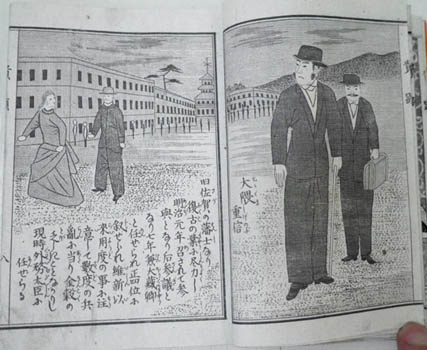

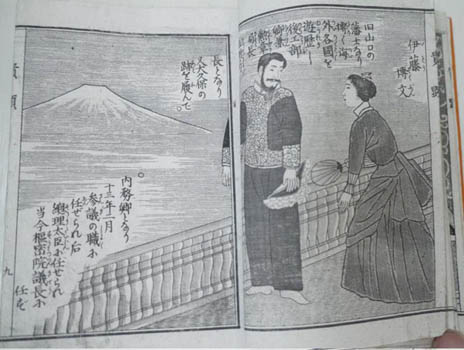

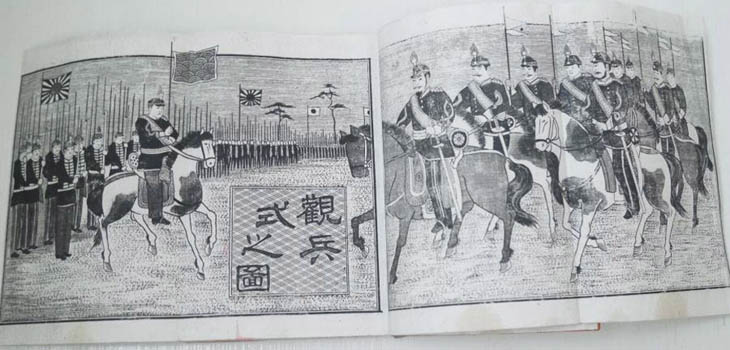

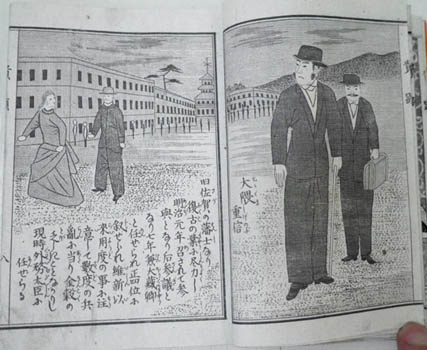

Baido Kunimasa [Utagawa Kunimasa IV]. [Meiji Kiken Kagami]. Tokyo, Hoeidi 1888 (Meiji 21). 12x9cm publisher's wrapper with title label (ink inscription on the back cover); 15 double folded leaves giving one single page, one gatefold quadruple page, and 15 double page woodcuts. Actually all but a couple of leaves are quadruple folded - the printed leaves around double folded leaves of heavier paper making the book tougher, made to be handled often. Au$300

A nifty little book, a portrait gallery of eminent figures of the Meiji. But captured in action, not the studio poses of so many 'Eminent Men' galleries. These are woodcuts but they are, with true modernity, cut to resemble engravings. Worldcat finds only the NDL copy.

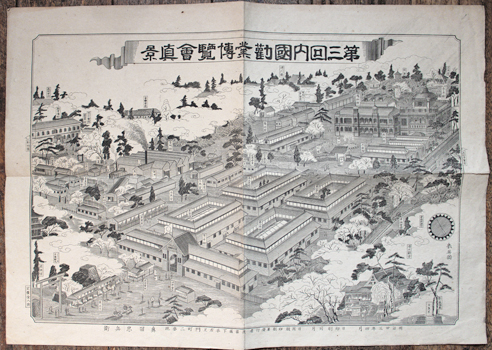

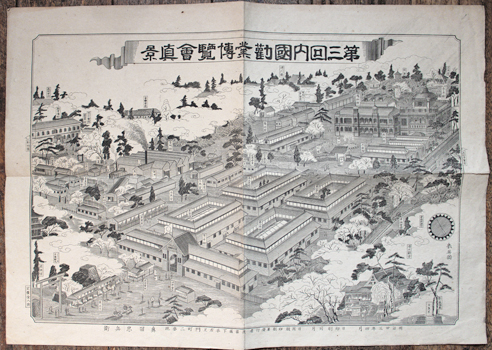

Exhibition - Tokyo 1890. [Dai Sankai Naikoku Kangyo Hakurankai Shinkei]. Okada Chubei 1890 (Meiji 23). 38x53cm engraving. Folded, rumpled with some smudges and a short tear in one margin. Au$125

The Third National Industrial Exhibition was, as often, a scaled back event: it was planned as an Asian exhibition. I can't find the first electric street car in Japan, unless what looks like an old locomotive with no smoke stack is a lazy artist's stand in. Still, there's no laziness anywhere else here.

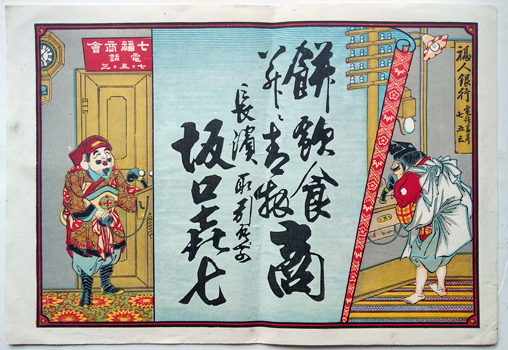

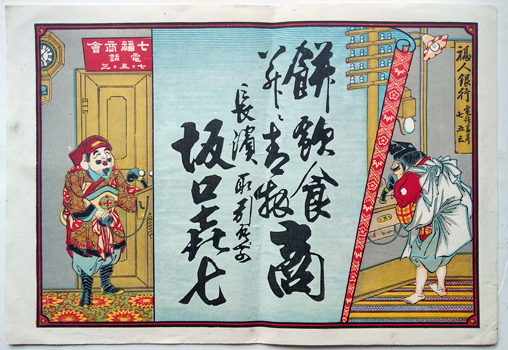

Telephone hikifuda. Hikifuda with lucky gods Ebisu and Daikokuten on the telephone. n.p. [Osaka? 189-?] Colour woodcut 26x38cm. A crooked fold and a few small marks; quite good and bright. Au$300

Ebisu and Daikokuten did embrace modernity - or rather, wanted to play with every new gadget and fashion - so naturally they would want to play on the telephone. Surely they had plenty of spirit messengers among their retinues. Apparently public telephones only became available in 1890, until then they were reserved for the government, police and select companies.

I can't read the centre panel which tells us who was selling what and I don't understand the signifance of 753 which is the number in both telephone booths and the banner on the right. Something to do with Shichi-Go-San? November 15? Sorry. But there would be no point to this hikifuda unless it was timely, that telephones were brand new, in the same way that this pair were pioneer joyriders in a motor car and donned military uniforms during the Russo-Japanese war.

Hikifuda - small posters or handbills - were usually produced with the text panel blank. The customer, usually a retailer, had their own details over printed, so the same image might sell fine silk or soy sauce.

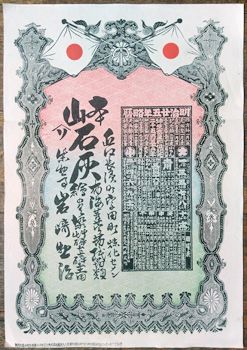

Hikifuda. ... [Yamaishihara ...] Osaka 1891 (Meiji 24). Colour woodcut 38x26cm. Two horizontal folds, a nice copy. Au$100

An example of a somewhat western aesthetic style (ie inspired by Japan) applied to the authoritive detail of a currency note or share certificate. In other words, here is a company or product to be trusted. Absolutely.

Hikifuda - small posters or handbills - were usually produced with the text panel blank. The customer, usually a retailer, had their own details over printed, so the same image might sell fine silk or soy sauce.

Yamaishihara is an area south west of Osaka and the timetable is for 1892. The rest is up to you.

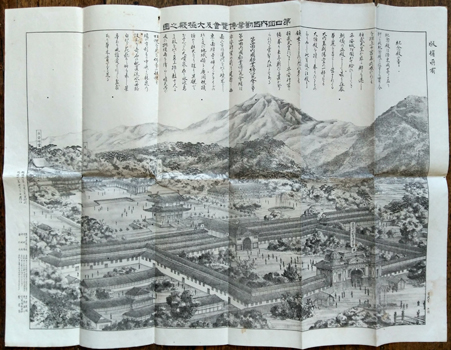

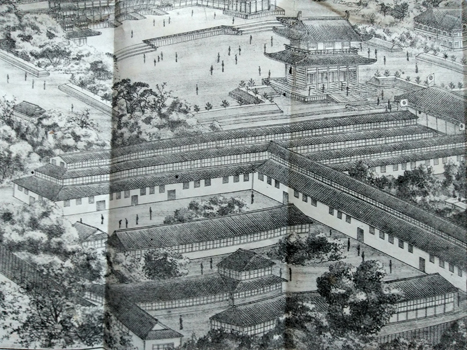

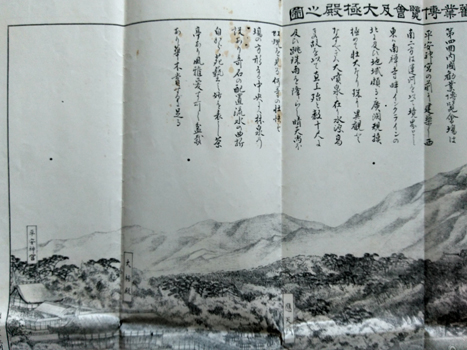

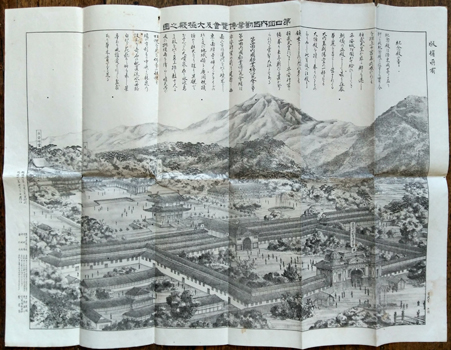

Exhibition, Kyoto 1895. Yoshiwara Takeo. [Daiyonkai Kangyo Hakurankai Taikyoku Zenzu?]. Kyoto, Ide Shozo 1895 (Meiji 28) Lithograph 42x56, folded. A scattering of small wormholes and signs of use; not bad. Au$125

A bird's-eye view of the 4th National Industrial Exhibition held in Kyoto from April to the end of July 1895. Five of these national exhibitions were held between 1877 and 1903; the first three in Tokyo and, after some provincial agitation, this in Kyoto and the fifth in Osaka. Each was bigger, better and more crowded than their predecessor.

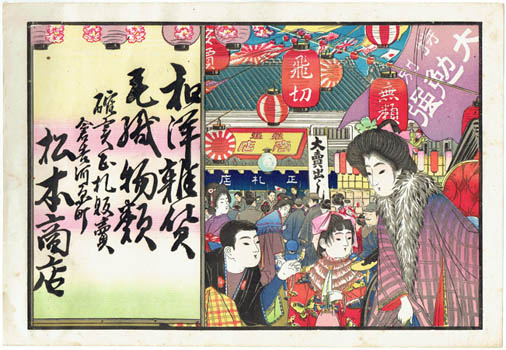

Hikifuda. Benkyo Shoten? [Wayo Zakka Keorimono-rui]. Hikifuda - or handbill - for a sale of Japanese and western wool textiles. n.p. [190-?]. Colour lithograph broadside 38x26cm. A touch browned round the edges. Au$100

An exuberant yet elegant thoroughly up to the minute snapshot of a stylish woman - with her painfully exquisite daughter - graciously acknowledging the attention of the shop boy at a busy warehouse sale of fabrics.

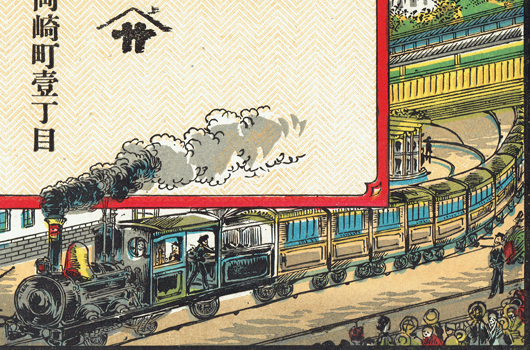

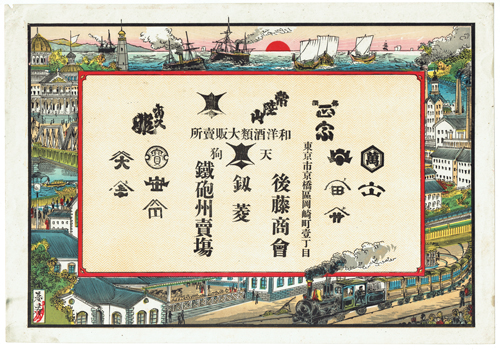

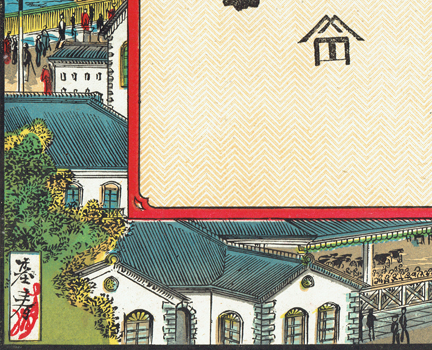

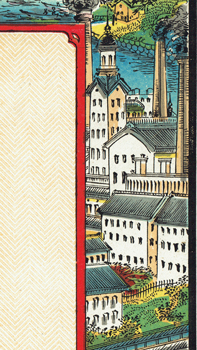

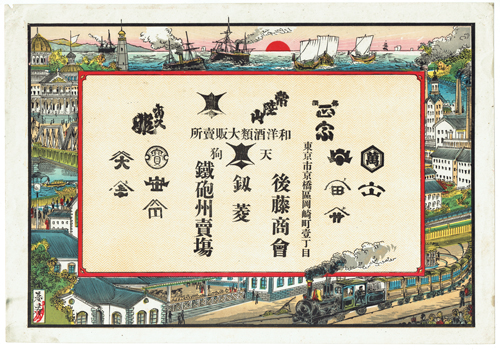

Hikifuda. [Goto Shokai]. n.p. [c1900] 26x38cm colour woodcut. Small knick from a top corner; a nice copy. Au$135

Bustling modern Japan is celebrated in this advertisement for the Japanese and western liquor merchants Goto Shokai. I presume it's the trademarks of the brands they handle that are displayed.

These hikifuda - small posters or handbills - were usually produced with the text panel blank. The customer, usually a retailer, had their own details over printed, so the same image might sell fine silk or soy sauce.

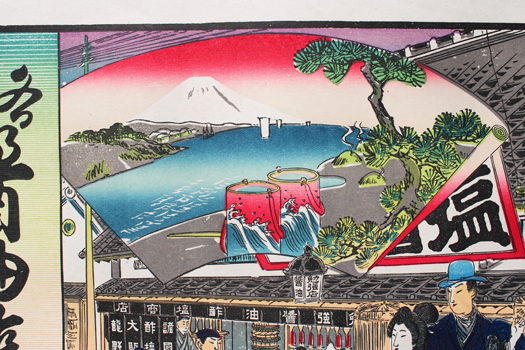

Hikifuda. ... [Shoyu Shio Sumi ...] np [190-?]. Colour lithograph 25x37cm. Pretty good. Au$150

An almost average street scene in late Meiji Japan but: without the telegraph poles and power lines, bowler hats and cyclist it could be a street scene generations earlier.

Hikifuda - small posters or handbills often handed out as seasonal gifts - were usually produced with the text panel blank. The customer, usually a retailer, had their own details over printed, so the same image might sell fine silk or soy sauce. This one, from a Nishinomiya (between Osaka and Kobe) dealer, indeed sells soy sauce, salt, sake and charcoal - tradition kept alive in the modern world.

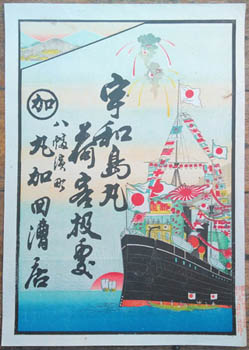

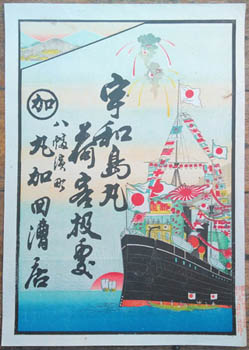

Hikifuda. Hikifuda of a ship bedecked with flags with fireworks overhead n.p.[190-?]. Colour woodcut 37x26cm. A small blotch in the upper right side, a nice copy. Au$185

An undeciphered by me hikifuda - large handbill or small poster - featuring some nautical celebration.

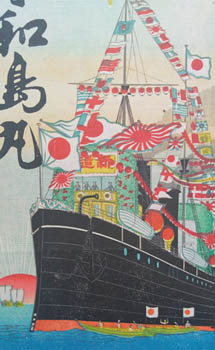

Hikifuda. Hikifuda of a ship against the rising sun. n.p. [c1900?]. Colour wood engraving? 26x36cm. Minor signs of use, quite good. Au$200

This handsome ship hikifuda - small poster or handbill - advertises something I can't read. It uses the western technique of wood engraving, a technique that had a brief run in commercial printing between traditional woodcuts and lithography.

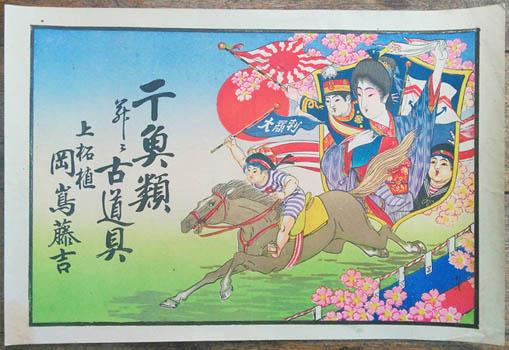

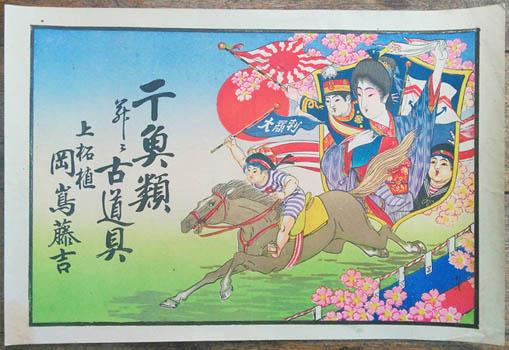

Hikifuda. Hikifuda of a boy sailor winning a horserace with a crown princess like mother and two other military children cheering. n.p. [190-?]. Colour lithograph 26x37cm. Minor signs of use, quite a good copy. Au$150

An exhilarating conjunction of sport, patriotism and those repulsive chubby infants so popular in the late Meiji period. I don't know what this hikifuda - a small poster or handbill - advertises but it is winning.

[1] 2 3 4   |